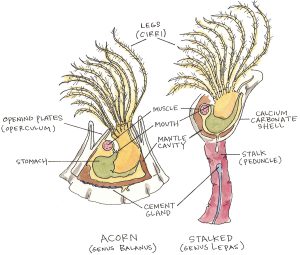

It was a typical weekday evening text for me—a video from a friend showing several interesting sea creatures and the message, “Do you know what these are? Some kind of mussel?” While the white-shelled creatures attached to a piece of driftwood looked like small clams, something in the recesses of my brain said, “barnacle.” A quick search confirmed my recollection—they were indeed barnacles, of the “goose” variety. Most barnacles are shaped like tiny, rocky volcanoes with a central opening that allows movement of the barnacle’s reproductive and feeding organs. Unlike clams, mussels, and other gastropods that use their large muscular foot to move around, barnacles are crustaceans that anchor permanently to a hard surface. They can be found frequently on boat hulls, pilings, debris, and the shells of other organisms.

The goose barnacle (Lepas anserifera), in particular, is a little different than the classic barnacle, in that its shell shape is more akin to a clam. Instead of filter feeding from cirri (feathery legs!) emerging from a central opening, goose (aka gooseneck) barnacles have a slit up the side from which their cirri reach to trap detritus and plankton. Their shells, usually no longer than 5 cm, sit atop a flexible stalk (known as a peduncle) that resembles a goose’s neck. In Spain and Portugal—and increasingly around the world—goose barnacles are a delicacy more prized than lobster and may fetch prices of $500/kilogram.

Interestingly enough, the inverse of this organism exists in bird form—the barnacle goose! A legend dating back to the 12th century has it that a pair of unusual geese showed up in Scotland that no one had seen before. Not having seen this type of goose emerge from any known eggs, locals deduced they must have hatched from the gooseneck-like barnacles that washed up on the shore. Hence the name, barnacle goose. A fascinating “scientific description” of the geese can be found in the Topographia Hiberniae or “Topography of Ireland” written by Gerald of Wales in 1188. The work covers natural history, culture, and religious stories of the country. An excerpt of his description of how barnacle geese hatch from barnacles hearkens back to the times when people relied fully on their own imaginations and observations to understand the natural world: “There are likewise here many birds called barnacles (barnacle geese) which nature produces in a wonderful manner, out of her ordinary course…Being at first, gummy excrescenses from pine-beams floating on the waters, and then enclosed in shells to secure their free growth, they hang by their beaks, like seaweeds attached to the timber.

Being in progress of time well covered with feathers, they either fall into the water or take their flight in the free air, their nourishment and growth being supplied, while they are bred in this very unaccountable and curious manner, from the juices of the wood in the sea-water. I have often seen with my own eyes more than a thousand minute embryos of birds of this species on the seashore, hanging from one piece of timber, covered with shells, and, already formed. No eggs are laid by these birds after copulation, as is the case with birds in general; the hen never sits on eggs to hatch them; in no corner of the world are they seen either to pair or to build nests.”

The crustacean and bird do resemble each other a wee bit, both being white, black, and gray, with an elegant head/shell attached to a long flexible neck. Barnacle geese do indeed hatch from eggs, though! The ancient description does ring true in several ways; goose barnacles are typically found hanging from driftwood and other flotsam washing up on the shore. Next time you’re at the beach, look closely on driftwood, sticks, and debris along the beach—odds are good that you’ll come across goose barnacles nearby.

4

4