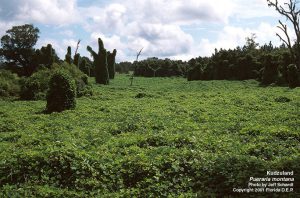

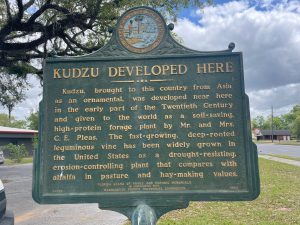

As I looked out the backseat of the car window as a kid in Mississippi, it covered everything along the highways—the gullies in the shade, the ridges and hills, abandoned buildings, telephone poles. My imaginative mind easily pretended the large mounds of vegetation were green giants or slow-moving dinosaurs. The trees underneath were unidentifiable, with canopies fully covered in vines. Nicknamed “the vine that ate the South,” kudzu (Puereria montana) was, like most invasive species, considered a great idea at one time. In fact, a historic monument at the Washington County Extension Office presents the best possible spin, describing it as a “soil-saving, high-protein forage plant” that “has been widely grown in the United States.” You can say that again.

Kudzu was widely grown because people intentionally planted it as forage and erosion control. Shortly thereafter it took root and took over, spreading well beyond those initial pastures at a rate no herd of cattle could keep in check. In the growing season, kudzu can literally grow one foot a day and result in 100-foot-long vines. The plants have deep roots (which do retain soil, hence the original plan) and can withstand drought, storing energy in huge tubers below the ground. These characteristics allow kudzu to outcompete native species, covering and shading them to the point they can no longer photosynthesize.

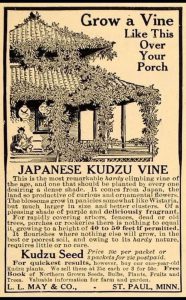

A native to China and Japan, kudzu was introduced into the United States at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, but truly took off in the South a few years later after a New Orleans expo. Objectively attractive, with 3 large lobed leaflets and red or purple flowers (which smell like grape soda!), it was touted as an attractive ornamental species with potential as a forage crop. Kudzu leaves and flowers are edible, and the roots can be eaten if cooked. While this is not done at any significant scale in the United States, I have seen kudzu jelly (a great substitute for grape jelly, I hear) sold in roadside stands. In its native range throughout east Asia, kudzu has been used in traditional medicines along with fiber, beauty products, and food.

A native to China and Japan, kudzu was introduced into the United States at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, but truly took off in the South a few years later after a New Orleans expo. Objectively attractive, with 3 large lobed leaflets and red or purple flowers (which smell like grape soda!), it was touted as an attractive ornamental species with potential as a forage crop. Kudzu leaves and flowers are edible, and the roots can be eaten if cooked. While this is not done at any significant scale in the United States, I have seen kudzu jelly (a great substitute for grape jelly, I hear) sold in roadside stands. In its native range throughout east Asia, kudzu has been used in traditional medicines along with fiber, beauty products, and food.

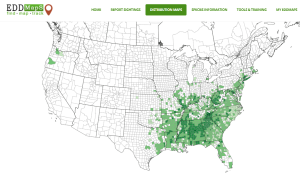

The US Soil Conservation Service promoted it widely throughout the 1930’s and 1950’s as an erosion control measure, even paying farmers to plant it. Seeds were available through mail-order, and the vine quickly took off. Today, the most intense kudzu infestations center around Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, but we do see it here in northwest Florida and there are pockets in the northeast, Pacific northwest, and upper Midwest. Besides reducing native biodiversity, kudzu hosts the kudzu bug and soybean rust fungus, both of which can wreak havoc on legume crops like lima beans and soybeans.

To manage smaller patches, goats or routine mowing can keep vines in check. Expansive patches can be cut down and sprayed with herbicides during the growing season. Research is being conducted on a biological control fungus which might provide some management. While kudzu is showy and obvious along roadsides in the deep south, it is not considered one of the most problematic species in the larger scheme of things. Kudzu rarely penetrates into the forest or wilder areas, sticking to “edges” of human civilization. There are newer air quality concerns with kudzu, however, as several studies have found that kudzu produces nitric oxide in the soil and can raise ozone levels in the immediate area around it. With annual temperatures rising due to climate change, vines are particularly well-suited to heat adaptation and growth of almost every type of invasive vine is expected to flourish.

4

4