We use the term, “living on the edge” to express a life of excitement, extremes, and perhaps a bit of danger. Frontier towns and port cities have this same dynamic, with a constant influx of new energy, people, and goods shuffling the status quo daily. It’s an apt description in the natural world, too. There is an entire academic body of work studying “edge effects” in ecological systems. Plant and animal communities formed along the border of at least two different ecosystems are dynamic—with constant battles over which community will dominate. Meanwhile, wildlife takes advantage of the contrast between two systems to improve their own circumstances; hiding in high brush for protection and feeding in the open land or water nearby. There’s a constant give-and-take at these edges, with nutrients and energy being exchanged from, say, the edge of a forestland to an adjacent grassland. In naturally occurring edges (alternately referred to as ecotones, buffer zones, or border areas), biodiversity is often high.

But when that exchange of information and energy is abruptly blocked—say by a border wall in human countries or vertical seawall in an aquatic one—the exchange is cut off. In a coastal system, wave energy building up against an armored shoreline pounds against a seawall. While this may prevent immediate damage to the land behind the wall, the energy is reflected down-shore, often causing severe erosion at the adjacent property. In addition, the unique ecosystem of emergent vegetation, crustaceans, birds, and fish is often eliminated, losing the rich “edge” community.

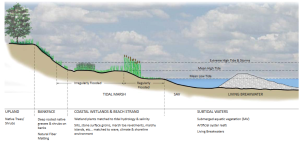

A “living shoreline” is a way to reestablish that lost habitat while providing an eco-friendly mechanism for erosion and storm protection, aesthetic improvement, and potential accretion of marsh and land growth. Living shorelines do not work in every situation (and of course sometimes people need fortifications to protect themselves from enemies), so each property must be analyzed inividually. High energy water bodies with extreme wave action or boat traffic would only support sandy beaches, and may need a more engineered solution to prevent erosion. But in the right circumstances and in concert with rock and oyster breakwaters, new shoreline plants can be successfully installed to create a sustainable, and living, shoreline.

Basic living shoreline designs typically include a breakwater built of rock or oysters, placed 10-25 feet waterward of the shoreline to slow down incoming waves. The two most commonly used plant species for living shorelines in our area include smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) and black needlerush (Juncus roemerianus). Cordgrass can handle the wettest and saltiest conditions, and tolerates being planted with its roots fully underwater. Black needlerush will thrive just upslope from the open water, providing a dense and tough source of stability once established.

In the state of Florida, a permit exemption can be granted for small living shoreline projects. This entails submitting a “Verification of Exemption Request” to the local Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) office. Step-by-step details of this process can be located at this link and include a sample narrative and drawings that show how a homeowner can submit the request. If your property is located within an aquatic preserve, you may be able to get installation and design help from the local FDEP staff, as discussed in this recent Science Hour program. The aquatic preserves in the western Panhandle are along Rocky Bayou in Okaloosa County, Yellow River Marsh (including parts of East and Blackwater Bays) in Santa Rosa County, and Ft. Pickens in Escambia County. Larger living shoreline and marsh creation projects (such as Project Greenshores in Pensacola) require permits and often require professional design assistance from contractors or environmental consultants. For more information on living shorelines, case studies, and photos, visit https://floridalivingshorelines.com/

4

4