In Lesson 2 we discussed how amphibians and reptiles modified the fish body design to live on dry ground. We also explained how the reptiles did a much better job of it. But there are some limits to the reptile design as well. For one, they are ectothermic (cold-blooded) like the fish. Temperature changes on dry ground are much greater than in the water. So, being ectothermic is a bit harder here. The obvious answer to this problem is to “become” endothermic (warm-blooded). Easier said than done right?

But what does it mean to be endothermic?

Endotherms can maintain their internal body temperature on demand. If the air temperature drops suddenly to 30°F ectotherm body temperatures will drop as well. As explained in another lesson, lower body temperatures mean lower metabolic rates which could mean loss of life.

Endotherms on the other hand, can maintain a body temperature even with the dropping air temperature. You and I have an internal body temperature of 98.6°F, not matter what the air temperature is.

Photo: Wikipedia

How do we do that?

The trick is to not loose the internal body heat your body produces during metabolism. Scales are not good insulators so any internal heat will be lost. One method used follows Bergmann’s Rule. This rule states that the greater the surface area is relation to volume; the more heat will escape (or be absorbed). In other words, the larger the body – the warmer the internal temperature. For a large animal, a larger body has more volume producing heat than surface area to lose it. We see this with animals that live in polar regions. Arctic fox, polar bears, and walrus are much larger than their cousins from warmer climates. Ectotherms can play this game as well. White sharks are much larger than many other species of sharks and, thus, can live in colder waters.

Photo: NOAA

To add to this, you have Allen’s Rule. This rule states that any extremity on the body (hands, feet, ears, nose, etc.) will increase heat loss. You may notice on cold winter days your hands, feet, and nose get cold faster than the rest of your body. You might notice that polar animals have very small ears compared to their warmer climate cousins. You will also notice many warmer climate animals will have larger ears to help lose heat if they live in the tropics. The African and Asian elephant for example.

So, size and extremities can be used by both endotherms and ectotherms to help control body temperature. But to KEEP a high body temperature at all times – to be truly endothermic – there is more. We need better insulation. We need to modify the scales. As mentioned above reptiles and fish both have scales, and these are not good insulators. Amphibians have nothing covering their skin, so they are at a loss. But birds… this leads us to birds.

Photo: University of Florida

When defining a bird, you only have to say one thing…. FEATHERS. No other animal on the planet has feathers. We tend to define birds by saying “wings and flight”. Not all birds fly – but they DO all have feathers.

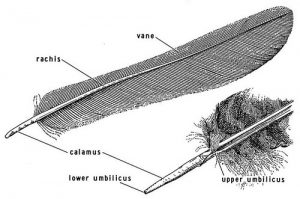

Feathers are actually modified scales. There is a hollow shaft will fringes extending off that are locked together like Velcro. These feathers come in three basic forms – (1) flight feathers (obviously for flying – and birds are TRUE fliers), (2) contour feathers (giving different species distinct shapes and looks – the crest on a cardinal for example, or the “ears” of an owl – these are not actually ears but just feathers that look like “horns” or ears), and (3) down feathers (these provide warmth and make the birds endothermic).

Image: Flickr

According to the American Museum of Natural History there are about 18,000 species of birds around the world – and they all have feathers and are endothermic. The modifications made by reptiles for life on land included lungs instead of gills, and the birds continue this. There are many species of diving birds, but all are holding their breath while doing so. Though most species of penguins hold their breath for less than 10 minutes, some can hold it 20 minutes – honestly, 10 minutes is impressive to me!

Another adaptation was the change from fins to legs. The birds kept this also… well, sort of. The hind limbs (legs) are still there but moved into a position for walking on two legs. The forelimbs have gone through a major change. What we see as wings are actually feathers extending from the fingers of their hands. Their forelimbs are VERY short compared to most vertebrates, but the fingers are very long. Well, some of the fingers are much longer than others. One finger extends well beyond the others and the flight feathers extend from this. Birds can use this modified forearm to actually fly. To enhance the ability to fly, the skeleton of birds is hollow and much lighter. Also, all birds lay eggs (oviparous). Holding on to the egg, or giving live birth, would certainly weigh the animal down and make flight very hard. So, they all lay eggs.

Many birds are carnivores. They may eat insects or worms, but they eat meat. Of course, there are many who eat seeds and fruit, and some are big time hunters. Hawks and owls are some of the most impressive predators in woodlands areas. And they do all of this without teeth! The bills of birds are modified to feed on specific foods. Cardinals have a beak that can crush seeds and acorns. Herons have bills that can knab quick moving crabs or fish. Eagles have bills that can tear flesh and meat from their prey. There could be a whole lesson on just birds and their bills. But it is food/feeding that separates the marine birds from others.

I asked a marine ornithologist (a scientist who studies birds) this question once – “how do you define a seabird? – are the birds living on our barrier islands considered seabirds?” His answer was no… they would not be. “Do they have to be able to swim?”. Again, no – they do not. He continued by saying “if it eats seafood it is a seabird. I liked this definition and have continued to use it. SEABIRDS EAT SEAFOOD.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

This marine ornithologist divided the seabirds into three groups. (1) inshore birds, (2) offshore birds, and (3) pelagic birds. Let’s look at the difference and some examples.

Inshore Birds

These are seabirds who live inshore, on the beach and feed in and around beaches. We see them all of the time. Pelicans, terns, gulls, herons, egrets, skimmers, plovers, sand pipers, loons, cormorants, and more. Each has a specialized bill for feeding on specific foods. Pelicans are famous for the large pouch on their beaks. Many think this pouch is used to hold food after capture and feed on later or give food to their young. Actually, it is used more like a net grabbing their prey as they dive into the Gulf. Once captured the seawater is drained by tilting the head and shaking it out. The fish are then swallowed before flight. As far as feeding their young – and this is true for most seabirds – they swallow their food and regurgitate this into the chick’s mouth when they reach the nest. Pelicans may regurgitate into the pouch and allow feeding there and they are also known to let their young peck at the pouch (called a gular pouch) to make it bleed, thus drinking the blood. This is extreme and usually happens when the parent cannot, for whatever reason, find and capture food.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Gulls and terns may capture small fish and return with them in their beaks for feeding young. Sand pipers and plovers are famous for probing the sand after waves wash out trying to grab small mollusk and crustaceans before the next wave comes in. There are also worms to be had here.

Feeding on shellfish brings up an interesting behavior. How does a vertebrate with no teeth get into the shell where the meat is? Many, like the oyster catcher, have blade like bills that can slip into the shell and cut the adductor muscle of an oyster like a pair of scissors – feeding once the shell pops open. But some birds, like gulls, will grab the clam or oyster and fly over parking lots where they drop the shell hoping it will crack open. They have been known to do this on bridges and houses, and they don’t care if your car is there or not.

There are many species of inshore birds that dive into the see to grab fish. The osprey is famous for doing this but going in “feet first” grabbing the fish with their strong sharp talons. Another interesting adaptation by the osprey is having a toe that can adjust to allow the fish to be moved into a position easier to fly, less drag from moving through the air. They carry the fish more like a bomb on a plane than 90° to this position as many other predatory birds must do.

Then there are the “wading birds”. Those with long legs to walk in water and broad feet to dissipate their weight so they can walk across soft sand or mud on the bay bottom. Most have long razor-like bills for grabbing fish and crabs. Ibis have curved bills for probing the mud for small crustaceans.

One of the neatest feeding behaviors is that of the black skimmer. This inshore bird flies very close to the waters surface. Their bill is very long, thin and blade like, and slightly curved. The lower jaw is slightly longer than the upper. As the bird flies just above the surface they will lower their lower jaw into the water creating is stream that attracts fish. They will quickly turn and fly back over the route grabbing any fish they attracted. It is really cool to watch.

Photo: Flickr

Offshore Birds

Offshore birds differ from inshore birds in that they return to land only to rest and breed. They will leave the beach early in the day and spend all day at sea fishing, much of the time out of the sight of land. The frigate bird is one such offshore bird. These relatively large black birds have a small gular pouch and are related to pelicans. They snatch their food from the surface and do not dive. They are known to be “pirates” and steal from other seabirds. Like most offshore birds, the wings are long and thin. The frigate bird’s wings are angular so that they look like the letter “M”, or “W” (your choice) when looking at them from the beach. They are most often seen during very windy days and are usually pretty high in the sky. Shearwaters and petrels are other examples of these offshore birds.

Photo: NOAA

Pelagic Birds

There are no true examples of these in the Pensacola area, but these are birds who leave land and not return until the next breeding season. Spending the entire year at sea feeding. The most famous of them is the albatross. These are large gull-looking birds with large wings (up to 7-foot wingspan). These long thin stiff wings are excellent for long distance flying but not good for landing and taking off. Actually, the wings are so large they cannot flap them as most birds do to begin flight. Rather, the head to the beach, open their wings, and run into the wind – taking off much like an airplane! Landing is even trickier. They slow their speed, drop their webbed feet as an air brake and basically crash onto the beach. They cannot flap their large wings and lightly set down as most birds do. Because of their comical landings they are often called “gooney birds”. Seeing one at sea was considered a sign of good luck by the ancient sailors. However, albatross, and other pelagic birds, are more common in the southern hemisphere where there is actually much more ocean than land.

No matter what type of seabird it is, they all must return to the land to breed. Most of these seabirds prefer to nest on islands to avoid predators. In fact, many will lay their eggs in small depressions on the sands of beaches knowing that no predators are around. The parents sit on them to make sure they do not overheat in the sun and the small chicks blend in well with the sand after birth.

However, in recent years this great plan has backfired. Humans are now on the islands. We have brought with us dogs and cats, which are a big problem for the birds. Even people walking the beach is a problem. The parents will fly off the nest to chase the predatory away (you) but leave either the chick, or the egg, exposed to sun and weather. With many people walking the beach all day the parents must do this more often than they want, and the eggs/chicks are exposed more often than they should. To top it all off, we have built bridges that have allowed predators like coyotes, fox, and raccoons to reach the islands and they are finding the eggs and chicks EASY meals. All of this has caused a decline in beach nesting birds.

Not all birds nest on the sand though. Egrets, herons, pelicans, and osprey, build nest in trees. Problems, though they exist, have been fewer for these species. Both parents take part in the raising the young. While one is out at sea hunting, the other is on the nest. It is true teamwork. It is a basic rule that animals produce more young than will survive but it is also true that the more parental care given the fewer eggs will be produced. Birds show a lot of parental care, so they do not lay a hundred eggs as sea turtles do but rather maybe 3-4. Even at this, not all will hatch and not all hatchlings will survive.

Seabirds are wonderful to watch and a good animal behavior study subject. They come out during the times of day we do, are easily seen, and their behaviors are very interesting. Birding is an easy and great hobby!

ACTIVITIES

- It is spring and time for nesting on our beaches. You can spend the day seeing how different ones you can find, watch them compete for the best spots on the beach for their nests, watch one parent leave while the other returns. REMEMBER THOUGH, IF THE FLY AT YOU – YOU ARE TOO CLOSE AND NEED TO BACK AWAY SO THEY WILL NOT BE OFF THE NEST FOR TOO LONG.

- It is also fun to watch them feed. Watching plovers and sand pipers peck through the sand is neat – watching to see if the next wave gets them! Another interesting behavior to watch is the great blue herons move around the fishermen looking for a handout or trying to sneak bait out of their bucket. Much fun.

- If you can’t make it to the beach you can see all of the spring nesting action in your own yard. Woodland songbirds in your neighborhood may not fly out to sea but other than that the behaviors are very similar and fun to watch.

0

0