If there is one thing we know in northwest Florida, it’s rain. As the wettest region of Florida, with an average annual rainfall total of 65+ inches, we also rival the Pacific northwest for highest national precipitation levels. We tend to have a “rainy season” of afternoon showers and tropical storms overlapping with hurricane season, but even winters can be quite rainy around here.

Knowing this about our climate, flooding has been an issue our communities have dealt with for centuries. Early settlers recognized the signs of low-lying, wet areas where floodwater collected, and chose to build on higher and drier ground. But as populations and our faith in engineering increased, we found ways to drain, pipe, and move water off the land so it did not flood new development. At least, we have tried.

When research started showing that pollutants in stormwater runoff were causing water quality problems in our bays and bayous, the state passed laws requiring stormwater treatment. In addition to treating runoff, these newly constructed ponds could often help alleviate flooding. The best treatment for stormwater is of course the natural one—simply allowing rain to hit the ground and absorb into the native soil. This way, the rainwater never picks up and transports pollutants from paved areas. But in the absence of that, stormwater ponds can help.

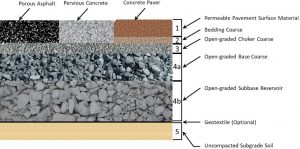

One relatively new technology that is gaining traction in the area is pervious pavement. This material functions like a hard surface for driving and parking while also absorbing rainwater like soil. It can be installed in place of or in addition to stormwater ponds and is dramatic in its efficiency. Watching a rainstorm from one of the county buildings with a mix of traditional paving and pervious, the difference is stark. Water falling on the regular pavement pools up, runs off, and takes with it a sheen of oil. The pervious pavement absorbs every drop of rainwater, leaving the surface nearly dry.

Warming global temperatures mean that “wet places get wetter and dry places get drier.” Being one of those wet and humid places, we can expect continued heavy and frequent rains. Recent records show a 27% increase in heavy rainfall in the past 60 years, and that what was once considered a “100-year storm” in the panhandle now occurs every 20 years. We will need all the help we can get, absorbing and treating those future downpours.

1

1