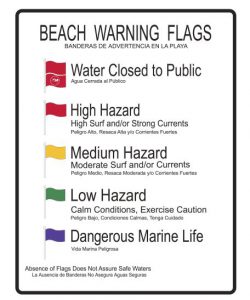

Oh, the dreaded purple flags at the beach—the idea of “dangerous sea life” can complicate a day on the water. While those flags might be flown if there are sharks hanging around nearby or red tide in the area, they much more likely indicate that jellyfish have floated in, particularly a “bloom” with hundreds or thousands present.

We have a wide variety of jellyfish in the Gulf, but I was struck recently by the symmetrical beauty of a small Atlantic sea nettle I found lying on Pensacola Beach. The rough waves of an approaching hurricane seemed to have torn its tentacles off, so all that remained was the circular “bell” (the top part of a jellyfish) with brown stripes radiating from the middle.

Like the terrestrial plant (stinging nettle) with which it shares a name, the sea nettle packs a powerful punch. The clear/pink tentacles hanging from the bell contain thousands of stinging cells (aka cnidocytes), which are released when touched. Many beach-goers have experienced a jellyfish sting without seeing any jellyfish around them. What accounts for this mystery pain? Often in rougher waters, gelatinous jellyfish (which are 95% water) can be broken up into small pieces. While nearly invisible, those stinging tentacles are still present, functional, and potent. Physical responses to sea nettle stings range from a burning itch that goes away in 15 minutes to a longer lasting rash. More serious reactions may include muscle cramps, sweating, or chest tightness. Meat tenderizer is always a good choice for any beach bag, as it breaks down the venom’s proteins and relieves the sting.

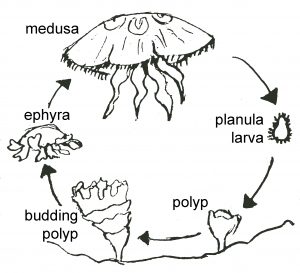

Intact, however, the sea nettle is quite striking. After larvae are released, it begins life as a sessile (nonmoving) polyp, usually growing on shells in the winter and spring. Free-floating medusae (the adult form of a jellyfish) are produced in the summer and fall. Full grown, they are the size of the more common moon jelly, with anywhere from a couple dozen to 40 tentacles. They feed mostly on comb jellies (look for a future post on those!), minnows, larvae of almost anything, and other jellyfish. Moving up the food chain, sea nettles are a favorite food of the spadefish.

Just three years ago, scientists discovered that there are actually two different species of what had been called the Atlantic Sea Nettle (Chrysaora quinquecirrha) for 175 years. The newly discovered relative prefers less-salty bay waters and is now known as the Bay Nettle (Chrysaora chesapeakei). These have primarily been seen in and around Chesapeake Bay (hence the clever name) but may have a larger range.

I have long maintained that October is the absolute best time of the year at our Gulf Coast beaches. The air is cooler, the water is still warm enough to get in, and the crowds are lighter. Keep an eye out for interesting sea life, and I hear the shelling is great right now after these storms. While it may take longer to get out to Pensacola Beach while the 3-Mile Bridge is out of commission, it’s well worth the trip once you arrive.

4

4