This is a guest post by Kelly Laplante, an undergraduate student and research assistant in the Dale Lab at the University of Florida Entomology and Nematology Department.

With the arrival of spring and warmer weather, you may have noticed a striped visitor flying around your garden or home landscape, exploring flowers and investigating holes in wooden fence posts. Your first thought may be that this is a bee or worrisome stinging wasp, but it is actually the red and black mason wasp (Pachodynerus erynnis), a welcomed guest.

This small, quick, solitary wasp can be easy to miss, and is one of many wasp species with similar black and red coloration found flying around Florida landscapes. If you can get close enough, the red and black mason wasp can be distinguished by its head, which is completely black behind its eyes. Other similar looking species have a red spot behind each eye. This extremely common wasp can be found throughout the southeastern U.S. for most of the year.

Are they dangerous?

When most people hear the word “wasp” they immediately become concerned. However, unlike their larger, more aggressive relatives like paper wasps (Polistes sp.), the red and black mason wasp is docile and won’t sting unless you force its hand – or rather, its abdomen. In fact, the red and black mason wasp is decidedly more friend than foe, as it serves many valuable ecological roles. For example, this wasp is an important pollinator for many native flowering plants in the southeast, like the saw palmetto (Serenoa repens).

What do they eat?

So, what else makes this wasp stand out among other common bees and wasps, and why should you be familiar with it? Well, have you ever planted squash or cucumbers and had pickleworms (Diaphania nitidalis) bore through the stems and fruit? Have you ever had your perfectly manicured lawn torn apart and eaten by fall armyworms (Spodoptera frugiperda) or sod webworms (Herpetogramma phaeopteralis)? Have your cabbages been ravaged by the cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni)? Luckily for you, female red and black mason wasps spend their days hunting live caterpillars to and feed to their offspring. Their prey include the species above and others widely regarded as plant pests. This means there are fewer pests (and subsequently less work) for you to deal with in your landscape. When they aren’t hunting for caterpillars, adult wasps gather food for themselves in the form of nectar from nearby flowering plants.

How they build their nests

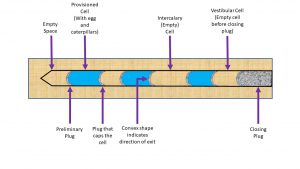

Red and black mason wasps create nests inside narrow tubes between half an inch and five inches deep. Within the tubes, the wasp will create individual cells separated by plugs of aggregated sand. She will lay a single egg in a cell, then go hunting for seven to ten caterpillars that she will stash inside the cell with her egg. Each time she snatches a caterpillar, she will carry it to the nest, and then paralyze it with a sting so that the caterpillar is defenseless when the wasp larva hatches and begins to eat it. The wasp will repeat this process until she reaches the outermost end of the tube, and then she will seal it off with a very thick sand plug to protect the larvae inside. Pretty gruesome, right?

Now you may be wondering how the wasp larva in the innermost cell of the nest can develop and emerge without disturbing the larva closest to the exit. It turns out that male red and black mason wasps develop more quickly than females, and the males are always laid in the outermost cells. The female wasp depositing the egg controls whether the egg gets fertilized or not, and since a fertilized egg becomes a female, she can decide where males and females are placed in the nest.

Okay, so how does a newly developed wasp know which way is out in complete darkness and without any illuminated “EXIT” signs? Fascinatingly, the mother wasp leaves behind directions when she constructs the sand plug cell dividers. Each sand plug is rough and convex on the side pointing towards the exit, and smooth and concave on the side pointing towards the back of the nest. A newly developed adult uses the shape of these sands plugs as a compass, chewing through the rough convex side to reach the exit.

If you build it, she will come

As Kevin Costner once said in Field of Dreams, “If you build it, he will come.” The “it” in this case is a pollinator nesting box, and the “he” is actually a she. Nesting boxes are structures used for attracting native bees and other pollinators. These structures are increasingly common and easy to purchase or make yourself! In Florida and other regions of the southeast, the red and black mason wasp is one of the first insects to move into a newly placed nesting box. Once they move in, they will get busy helping your garden!

For tips on making a pollinator nesting box, check out these links: (Pollinator Hotels) or (Creating Pollinator Nesting Boxes to Help Native Bees). To specifically target the red and black mason wasp, holes should be drilled with diameters of 3/16 to 1/4 inches (4.8 mm to 6.4 mm) to a depth between half an inch and five inches (14 mm to 125mm).

Curious about this insect or others common around your home landscape?

Check out the ‘Helpful, Harmful, Harmless’ identification booklet for sale at the UF/IFAS Extension Bookstore and other similar publications at dalelab.org.

1

1