By Tatiana Sanchez1 and Remy Powell2

1Commercial Horticulture Agent, UF/IFAS Extension Alachua County; 2UF/IFAS Extension Intern, Public Health Master student.

I was sitting on my in-law’s porch late in the afternoon when I noticed tiny “flies” flying around. Their house, in north Gainesville, is surrounded by a woody area with oaks, a few cypresses, wild cherries, sassafras, and pines. I reached out to take a closer look and grabbed one of the bugs. After closer inspection, this tiny insect was not a fly, it was a little beetle, an ambrosia beetle.

Ever since the redbay ambrosia beetle was found to be the vector of a terrible disease in the avocado family (Lauraceae), Laurel wilt, ambrosia beetles gained a bad reputation but in fact, they are fascinating.

Ambrosia beetles come from two different families of bark beetles [Curculionidae: Platypodidae and Curculionidae: Scolytinae]. Depending on the species there can be multiple generations per year or just one. Like any other beetle, ambrosia beetles have a complete metamorphosis which includes four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult.

There are many different species of ambrosia beetles. Typically, ambrosia beetles will attack trees that are weakened, dying, or stressed but some species can cause damage to healthy hosts. The red bay ambrosia beetle sneaked into the United States and once established, it had a relatively easy time spreading.

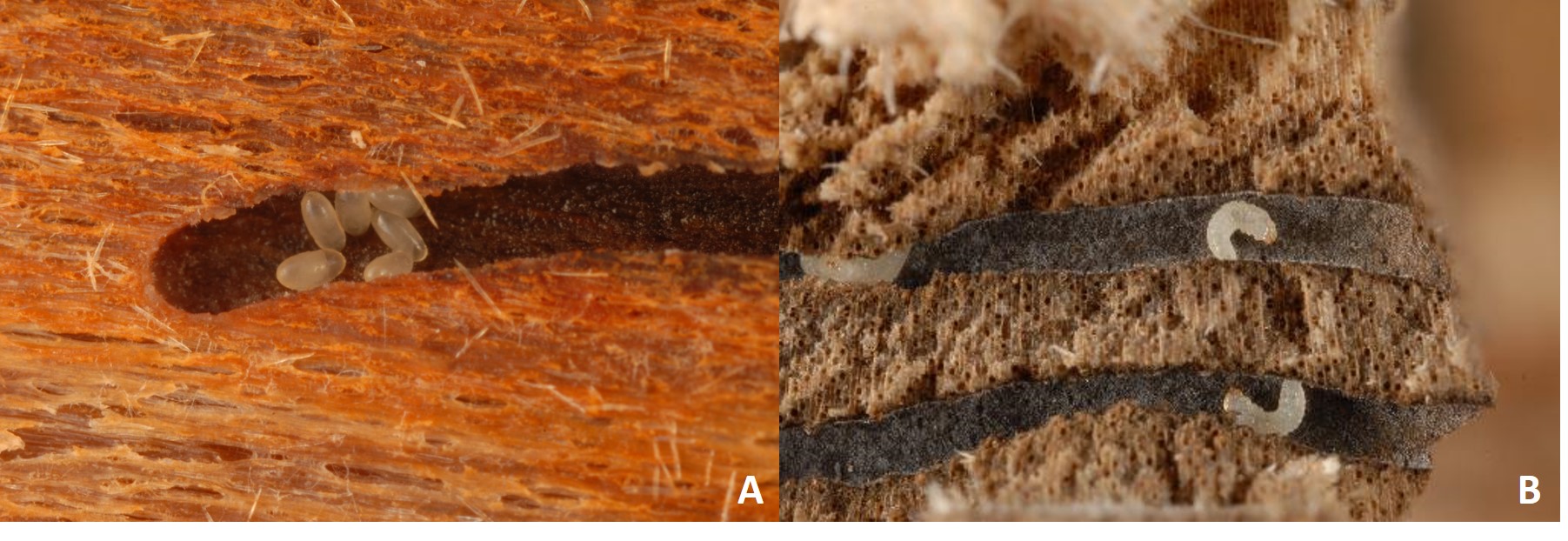

After a beetle lands on a suitable tree, it bores into it and releases spores from a fungus carried in a specialized organ known as mycangia. Isn’t that cool! They evolved this specialized structure so they can bring a fungus with them wherever they go. The fungus germinates and colonizes the plant tissue from which it extracts nutrients. The fungus gets to move around while the beetles feed on the fungus.

Some of the common signs of damage include pinhole defects, dark staining in wood, and galleries. Eventually, vascular transport is disrupted by the boring and blockage of the xylem by the fungus. As the beetles bore into the wood, they also create an opening for plant pathogens to the further detriment of the attacked tree.

The 15-year-old sassafras in my in-law’s yard succumbed to Laurel wilt disease vectored by the exotic red bay ambrosia beetle. Suckers from around the stump come up only to die back.

0

0