By: Bethany Wight, Biologist

UF/IFAS Range Cattle Research and Education Center

Elizabeth “Liz” Rose grew up in a residential area near the Minneapolis, MN chain of lakes. Growing up she spent most of her time outdoors, going on nature walks, exploring parks and camping. During high school she excelled in AP biology and science.

“Even in high school I knew I wanted to do something conservation related.”

Liz attended Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, NY and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Environmental Science in 2008. The environmental program was very focused on water resources and conservation, however, Liz was lucky to be able to study abroad in Costa Rica in 2006 during her junior year. During her study abroad Liz was introduced to avian studies and gained experience with mist netting, handling and sampling birds.

“I originally thought I wanted to work in international agriculture and sustainability, but after studying abroad in Costa Rica and working on bird conservation I realized I was more interested in wildlife conservation, specifically ornithology.”

After receiving her BA, Liz worked as a veterinary assistant in upstate NY and then a nanny in MN, but she soon transitioned to working in a variety of technical field jobs. Her first field job in 2009 was tracking whip-poor-wills on the Camp Edwards Military Base in Cape Cod, MA. The project focused on large tracts of military land. It took two months to catch 10 whip-poor-wills as they nest on ground leaf litter and are very good at camouflage. After they captured the birds they were equipped with telemetry backpacks to estimate habitat use and home range size. Her next field job in 2010 took her to Millbrook, NY working for Texas Tech University monitoring ground nesting birds. Then in 2010-2011 she moved to CT with her now husband Jeff to work for a state agency looking at how invasive understory shrubs change community structure and how that in turn impacts mice and ticks, specifically Lyme disease. Here she gained experience with small mammal trapping, as well invasive shrub control. Her last field job (and her favorite!) was studying island scrub jays on the Channel Islands off the CA coast. She lived on an island for three months, leaving only once to get groceries. The project involved driving around the island trapping, tracking and monitoring the jay population. Her interest in avian research increased.

“Being a seasonal field technician can be a financial struggle as such positions often don’t pay well and are usually temporary, but at the same time you need to gain practical experience and these jobs can also be very personally rewarding. Unfortunately, it’s one of the many barriers to entry in this field.”

Liz started applying to graduate schools in 2011 and only got in to UF because she received a National Science Foundation (NSF) graduate research fellowship and started her master’s degree (MS) at UF in the fall of 2012. The NSF fellowship allowed her to bring her own funding (it can take a while, but don’t give up!). She came to UF because she had been talking with, Katie Sieving, her soon to be MS advisor for a while, and her lab helped Liz edit and refine her fellowship application. She also came because the program allowed her the freedom to study any number of topics and she thought Florida was an amazing place to study wildlife. For her MS research, Liz studied the Florida scrub jay population in Ocala National Forest, collaborating with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). They looked at how vegetation structure, specifically the density and height of pines, affects the jay’s response to predators like the Cooper’s Hawk. They found that jays tended to show more defensive or mobbing behavior in older developed forest stands versus managed, more natural forest stands. Liz was also a teaching assistant for two semesters in the environmental science laboratory. She graduated with her Masters of Science in 2014.

After her MS degree, Liz decided to stay at UF and move her research focus towards wildlife conservation in highly modified habitats, which is a big thing in Florida! While researching different Florida species she came across the Florida burrowing owl, which was under consideration at the time for listing as Threatened by FWC. Liz noticed that there was a lot of information gaps because most of the previous research was conducted in suburban areas where the owls are much more accessible. However, historically, the owls used dry prairie habitat, which has greatly diminished across the state. The owls are able to shift their habitat to move into cattle ranches, drained areas, and modified grasslands. So Liz reached out to FWC and got in contact with Dr. Raoul Boughton of the RCREC’s Rangeland Wildlife Program. In addition, Dr. Boughton, and previous students, had relationships with cattle ranchers that had owls on their property.

“With my project, I wanted to fill in some knowledge gaps in the biology of owls on cattle ranches while also comparing them to urban owls too see how they adjust their ecology and behavior to occupy developed areas like Cape Coral and Marco Island, FL.”

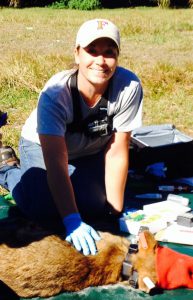

Liz’s PhD project included 7 study areas, five cattle ranches and two urban areas in Cape Coral and Marco Island. Her project has three main objectives: 1) determine how urban and rural owls differ in reproduction and space use 2) collect and examine basic biological information on rural owls 3) examine how urban development impacts owl density and habitat use within urban populations. Every spring for three and half years Liz would drive around conducting survey transects to identify owls on the multiple study areas. As is common in many avian studies, Liz attempted to uniquely band all of the owls she found in order to track individuals over time. The owls were captured using one way entry traps at the owls burrow. Then owls were banded with a metal federal USGS band as well as unique color combination bands. Measurements were taken on the owls body length and wing span and a blood sample was collected for later genetic analyses. For a sub-set of urban and rural owls Liz also monitored reproduction by counting the number of juveniles produced and successfully fledged. She also attached GPS backpacks to a sub-set of male owls to examine their habitat and resource use while they were provisioning young.

Liz’s results indicate that while Burrowing Owls on cattle ranches need high and dry habitat to make a burrow, they are traveling to wetlands and agricultural ditches during their nighttime forays. Many breeding males even leave ranch properties to forage in other agricultural areas. This indicates that wetlands and other water resources are potentially important sources of food for breeding Burrowing Owls, and that not only ranches but also the landscapes around them are potentially significant. For the urban owls Liz found that there was less variability among males and they tend to make shorter trips away from the nest burrow at night. The urban owls prefer to use vacant lots for digging their burrows, but were mostly foraging in developed residential yards that had irrigation, likely because there is a higher concentration of the owls preferred prey, arthropods and non-native vertebrates such as brown anoles and Cuban tree frogs. While the urban owl population appears stable in the short term, as development increases the reduction in open space and vacant lots may impact their ability to successfully nest and reproduce.

Liz is planning to graduate in the summer or fall of 2020. When she is not conducting research she enjoys cooking, walking her dog and some attempts at gardening.

“I’d like to have a career outside of academia. I would like to work in conservation on private/agricultural lands, so hopefully I can continue to research how wildlife can be maintained in these working landscapes.”

Liz’s projects were funded by FWC and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

This was written by Bethany Wight, a biological scientist at the UF/IFAS Range Cattle REC in Ona, FL. If you have questions please contact her at bwight@ufl.edu.

For more information on Liz’s burrowing owl projects visit:

https://www.rangelandwildlife.com/burrowing-owl-projects.html

1

1