It sounds crazy, but one of my favorite places to be is in the middle of a salt marsh. Sure, there may be gnats and mosquitoes, shoe-sucking, rotten-egg-smelling sulfurous muck, and no shade. But the sense of being completely away from civilization and on the water has always held great appeal to me. It is, of course, much easier to explore the edges of marshes on a kayak or paddleboard than by foot. A quiet paddle through salt marshes and creeks any time of the year is sure to yield wildlife sightings. Wading birds, fish, blue crabs, marsh rabbits, and diamondback terrapins all depend on these highly productive habitats for food and shelter.

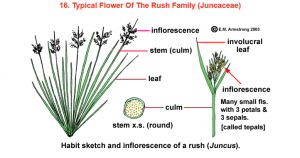

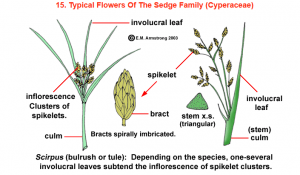

Down in south Florida and in parts of coastal Louisiana, healthy salt marshes are populated predominantly by mangrove trees along the shoreline. But up here (for now, depending on climate change) the emergent vegetation along salt and freshwater marshes is dominated by grass-like plants. This vegetation is usually a type of bulrush, sedge, cordgrass, or needlerush. If you ever took a Master Naturalist class from me, you’ve heard the nerdy botanical rhyme, “sedges have edges, rushes are round, and grasses have nodes all the way to the ground.” When an individual blade is cut in a cross-section, sedges will be shaped in a triangle, rushes are circular and somewhat hollow, and grasses are flat with other blades branching off at nodes. Their common names may not reflect their botanical category—beakrush and sawgrass are sedges, for example—thus the need for scientific names.

In the salt marshes of the coastal Atlantic and Gulf, one of the most noticeable plants along the shoreline is black needlerush (Juncus roemerianus). Dark, rigid, and tall (I’ve been in stands over my head), this green-gray-black rush forms a dense thicket along the shoreline. Thriving with soaking wet roots and in high concentrations of salt is difficult, so of course the plant has adapted to these conditions. Its fibrous roots grow deep in the muck, helping to stabilize neighboring plants, which are also inundated constantly by flowing water.

Dealing with salt is a major issue for coastal plants. If you look closely at the tip of an individual rush, you’ll see it looks dead, and there may be actual salt crystals accumulating on the plant. The needlerush tips look this way because the plant uses special glands to remove salt, excreting it and essentially dumping it at the tip of each plant.

Speaking of those pointy tips, these are substantial plants and can be painful if touched with much force. Over the years I’ve spent many hours wading through these marshes, and it’s important never to bend down in a Juncus marsh or you’ll get a stab to the face or eyeball! Often, I’ve walked through the marsh with my arms straight up in the air to prevent jabs to the underarm. Not only is it a physically tough plant, but recent studies related to the 2010 oil spill have shown it can break down the hydrocarbons in petroleum when exposed to diesel fuel. This has positive implications for remediation and recovery polluted water bodies.

0

0