Giant invasive snakes: The problem with invasive species

By now, we have all heard of the giant invasive snakes, such as the Burmese pythons now found in Everglades National Park. Like many animal species that become invasive, these pythons have traveled from a far-away location, often as part of the pet trade, and been released here in Florida. If the environment is just right, then these non-native species may thrive, sometimes without a natural predator, and having the ability to reproduce and survive in Florida’s warm, subtropical climate. Non-native plants and animals don’t receive the designation of “invasive” until they establish a viable breeding population in their new home AND cause harm to our native ecosystems or economy. Burmese pythons have been breeding in South Florida for over twenty years and the USGS now estimates their numbers to be in the tens of thousands. They may grow up to twenty feet in length and weigh 200 pounds. Over 60 species of native animals have been found in the stomachs of these giant snakes, and the population of small mammals has been greatly reduced in areas where they are now living.

Invasive species are expensive

Once a non-native species becomes invasive, there might still be a chance to eradicate it. But if their population growth continues and eventually becomes exponential, we can pass our opportunity to eradicate it. We are than left trying to manage and control the effects on our native species and natural resources. In Florida, invasive species negatively impact major economic industries such as agriculture, ecotourism, recreation, and fisheries.

Lionfish illustrate a perfect storm of economic and ecosystem damage. According to the US Fish & Wildlife Service, it is estimated that there are more than 1,000 lionfish per acre in some locations. Lionfish are voracious predators who consume native reef fish and decrease populations by 79 percent. Their prey includes important commercial and recreational fish species such as snapper and grouper. Consequences of this invader include harm to fisheries, coral reef conservation, and tourism. In a similar example from the Great Lakes, the federal government invested $78.5 million in 2010 to prevent the introduction of Asian carp to the Great Lakes. Like lionfish in the south, Asian carp are a threat to Great Lakes fisheries and endangered aquatic species. These threats and damages add up. Pimental, et. al. (2005) indicated that the US spends more than $120 billion a year in mitigating invasive species damage.

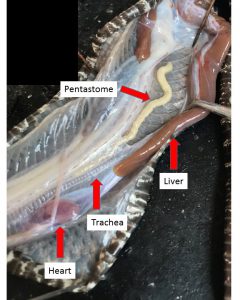

Invasive snakes carry a new threat

A recently published study by Melissa Miller, et al. sheds new light on another invader carried in the bodies of Burmese pythons. Raillietiella orientalis, or R. orientalis for short, is what’s called a pentastome parasite. Penta stands for the 5 and stome means “mouth”. There are five mouth-shaped areas on the underside of this worm-like parasite- which isn’t really a worm, and doesn’t have five mouths. Pentasomes are more closely related to crustaceans like crabs and lobsters, and its five mouths are actually 1 mouth and 2 pairs of jointed legs on each side of its mouth. Interesting, right?

R. orientalis is a lung parasite. In some ways it reminds me of heartworm in dogs, and in some ways it reminds me of Covid-19. Why? Because like heartworm in dogs, R. orientalis affects a major organ system. Heartworm affects the heart and circulatory system. R. orientalis effects the respiratory system, causing lung inflammation and infections, decreased function (or ability to breathe), and eventually may affect the overall health of snakes leading to decreased growth and reproduction or even death. How does it remind me of Covid-19? R. orientalis is a novel parasite to our native snakes. So just like Covid-19 is a new virus our human immune systems have never seen, R. orientalis is new to the immune systems of our native snakes and we do not know the extent that it will affect native snake populations. When a host organism and a parasite evolve over time together, the host develops ways to adapt or resist the parasite, but for our Florida snakes, R. orientalis was an unknown threat until recently.

What does the science say?

Dr. Miller and her colleagues first studied this novel parasite in native snakes in 2017, determining through DNA evidence that the parasite was, indeed, our friend Raillietiella orientalis. In their January 2020 study published in Ecosphere, Miller, et. al. studied 1003 Burmese pythons and 523 native snakes. R. orientalis was found in 13 species of the 26 native snake species studied. Dr. Farrell, a researcher at Stetson University, has also confirmed R. orientalis in a fourteenth native species. Dr. Farrell states “The work Melissa Miller and her collaborators have just published is incredible important for conservation. They have found a dangerous invasive parasite, documented its high abundance, and shown it is rapidly spreading out of South Florida.” (personal communication, June 29, 2020)

Other worrisome findings include the parasite being found in native snakes 350km further north, than the pythons infected with the parasite. Also, female parasites found in native snakes were longer than the females found in the pythons. Longer length is correlated with increased egg size and production, which could mean more parasites. And one more piece of bad news, the top three species of native snakes that were infected, are distributed throughout much of North America. These findings would suggest it is possible, and even likely, that R. orientalis has found a stable new host in our native snake species and may continue to infect snakes without needing Burmese pythons as their primary host.

What we don’t know…

More research will need to continue to determine the long term consequences of this novel parasite to our native snakes. Just how much of an impact will it have? We’re not sure yet, but researchers suggest this may be the cause of the population decline in pygmy rattlesnakes in South Florida. We’re also not sure what animal may be the intermediate host. Snakes carry the adult parasite and the eggs are passed out of their digestive systems. Intermediate hosts swallow the parasite eggs which grow into larvae and eventually adults. When the intermediate host is eaten, the adult parasite then infects the lungs of its primary host, the snake. Looking at what animals are eaten by the infected snake species, suggests that the intermediate host may be small mammals, frogs, or lizards.

Other fun facts

- most northern snake infected was a red rat, or corn snake found in Lake County

- no infected snakes were found north of Alachua County… yet.

- most common species of infected snakes: cottonmouth, banded water snake, and Eastern garter snake

Can’t get enough of this fun topic and want more?

- Watch Bay News 9 interview Dr. Clements

- Watch a Youtube video of pentastome parasites in a pygmy rattlesnake lung. Courtesy: Terry Farrell, Stetson University.

What can you do?

Burmese pythons can no longer be acquired as pets, and a permit is required to possess pythons for the purposes of commercial sales, public exhibition, or research. Read more about Burmese pythons at https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/profiles/reptiles/snakes/burmese-python/

If you see a python, try to take a photo, get a GPS location, and a date/time and upload to the IveGot1 app or on their website.

References

Miller, M. A., J. M. Kinsella, R. W. Snow, B. G. Falk, R. N. Reed, S. M. Goetz, F. J. Mazzotti, C. Guyer, and C. M. Romagosa. 2020. Highly competent native snake hosts extend the range of an introduced parasite beyond its invasive Burmese python host. Ecosphere 11(6):e03153. 10.1002/ecs2.3153

Farrell, T., Agugliaro, J., Walden, H., Wellehan, J., Childress, A., Lind, C. (2019). Spillover of Pentastome Parasites from Invasive Burmese Pythons (Python bivittatus) to Pygmy Rattlesnakes (Sistrurus miliarius), Extending Parasite Range in Florida, USA. Herpetological Review. 50. 73-76.

Miller MA, Kinsella JM, Snow RW, et al. Parasite spillover: indirect effects of invasive Burmese pythons. Ecol Evol. 2018;8:830–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3557

An Equal Opportunity Institution. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Nick T. Place, dean for UF/IFAS Extension. Sarasota County prohibits discrimination in all services, programs or activities. View the complete policy at www.scgov.net/ADA.

0

0