Feeding our horses is typically the largest expense in horse ownership, but feeding them according to their nutrient demands could offer some cost savings. Selecting a good quality hay for our horses often becomes a battle of which product is the greenest color and smells the “best”. However, these are merely clues and actually tell very little about the nutritional quality of the forage.

Feeding our horses is typically the largest expense in horse ownership, but feeding them according to their nutrient demands could offer some cost savings. Selecting a good quality hay for our horses often becomes a battle of which product is the greenest color and smells the “best”. However, these are merely clues and actually tell very little about the nutritional quality of the forage.

Hay quality

The idea of “forage fed and grain finished” should be the forefront of decision making when evaluating the equine diet. Forage and pasture can provide a significant portion of the nutrition required for most classes of horses, however, under many circumstances some of this forage inevitably must come in the form of hay. If pasture management is prioritized and stocking rates are adequate, horses can consume 1.5-2.0% of their body weight with full time grazing; which satisfies many classes of nutritional requirements (notably digestible energy and crude protein) for various horses such as those at maintenance, in light to moderate exercise, and even early-mid gestation.

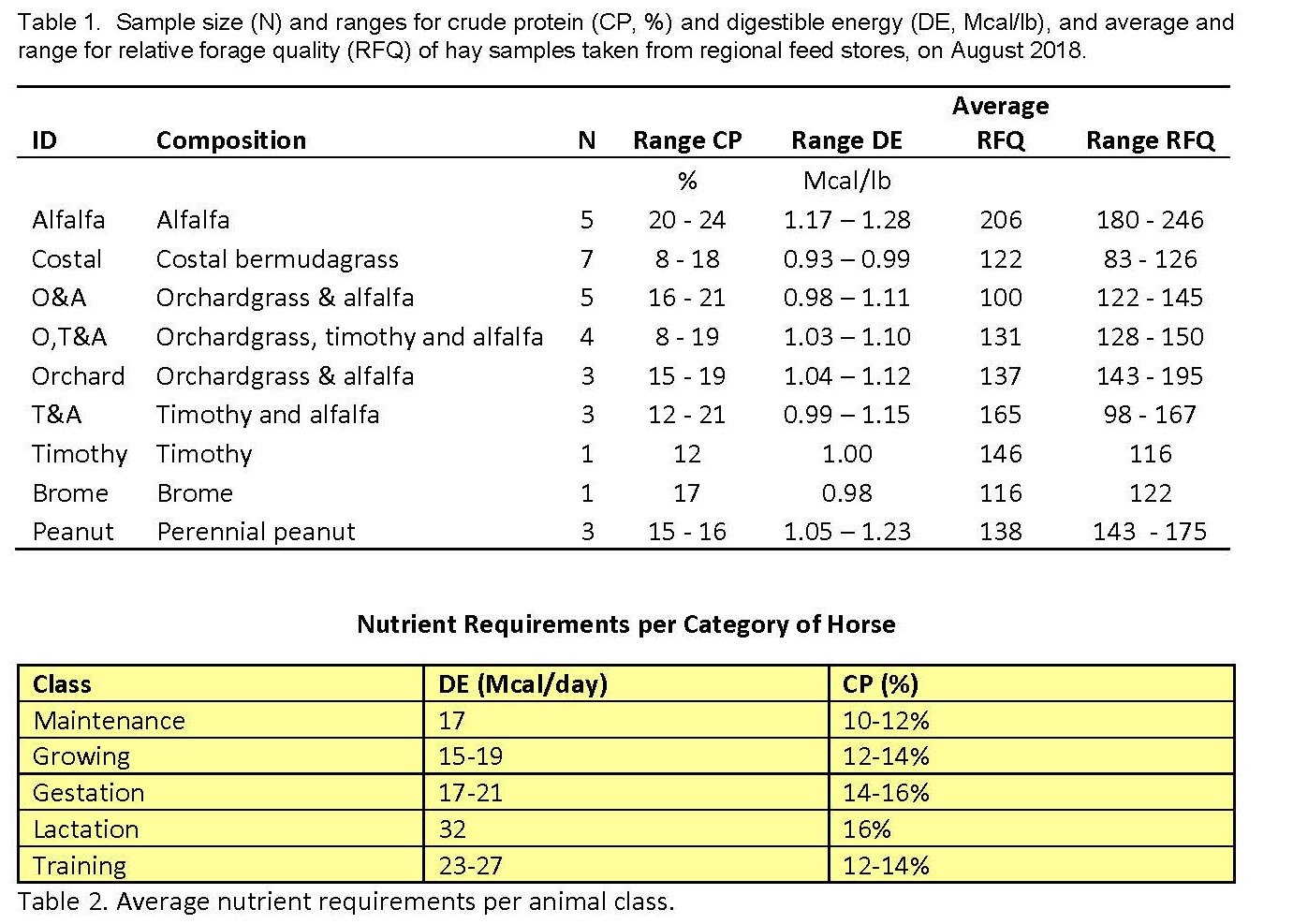

The choice of hay has to take into account the horse diet requirements (see Table 2), which is different for each horse category, and all other components of the diet (i.e. pasture, concentrate, minerals, etc.). The only way to assure hay quality is through laboratory testing. Visual and olfactory cues can help determine if the hay is clean of weeds and free of mold, but will not give much further information. Good quality horse hay should be mold and dust-free and should not contain extraneous materials such as weeds and poisonous plants. Hay quality is variable from specie to specie as well as cutting to cutting, seldom will you receive an exactly uniform product each purchase.

Key nutritional measures of harvested forage include; crude protein, digestible energy, crude fiber, non-structural carbohydrates, and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF). The Relative Forage Quality (RFQ) is a parameter that can be used to compare different forage analyses. It includes not only information on the nutritional value but also an estimate of intake based on digestibility, thus provides a good index to compare potential animal performance between forages.

There are many factors that affect the composition of forages used for hay, these include the type of forage (legume vs. grass), warm-season vs. cool season grasses, and the stage of maturity at harvest. In general, a hay considered “high quality” would be high in protein (>14%), have a low NDF/ADF ratio and be low in lignin. These forages will be less mature, more digestible and highly palatable, and horses with high nutrient requirements would benefit from these hay types.

On the other hand, low-quality forages and hay can be an option for horses that need to lose weight or have low maintenance requirements. The idea that the only quality hay available are those that are not grown in Florida such as alfalfa, orchard grass, or timothy is a misconception. While these hay types generally have high nutritional value, they may not always be worth the higher price tag that comes along with them if you can meet nutritional goals with hay types harvested more locally, such as bermudagrasses or perennial peanut in the warm-season, or oat hay in the cool-season. In fact, bermudagrass hay can have high protein as well (see range on Table 1). Using the “scale of greenness” to gauge hay quality can be quite misleading, many times a lab analysis will reveal forage quality of less aesthetic hays to equal or greater value than similar types that appear better because they possess a darker shade of green.

Can good quality horse hay be grown in Florida?

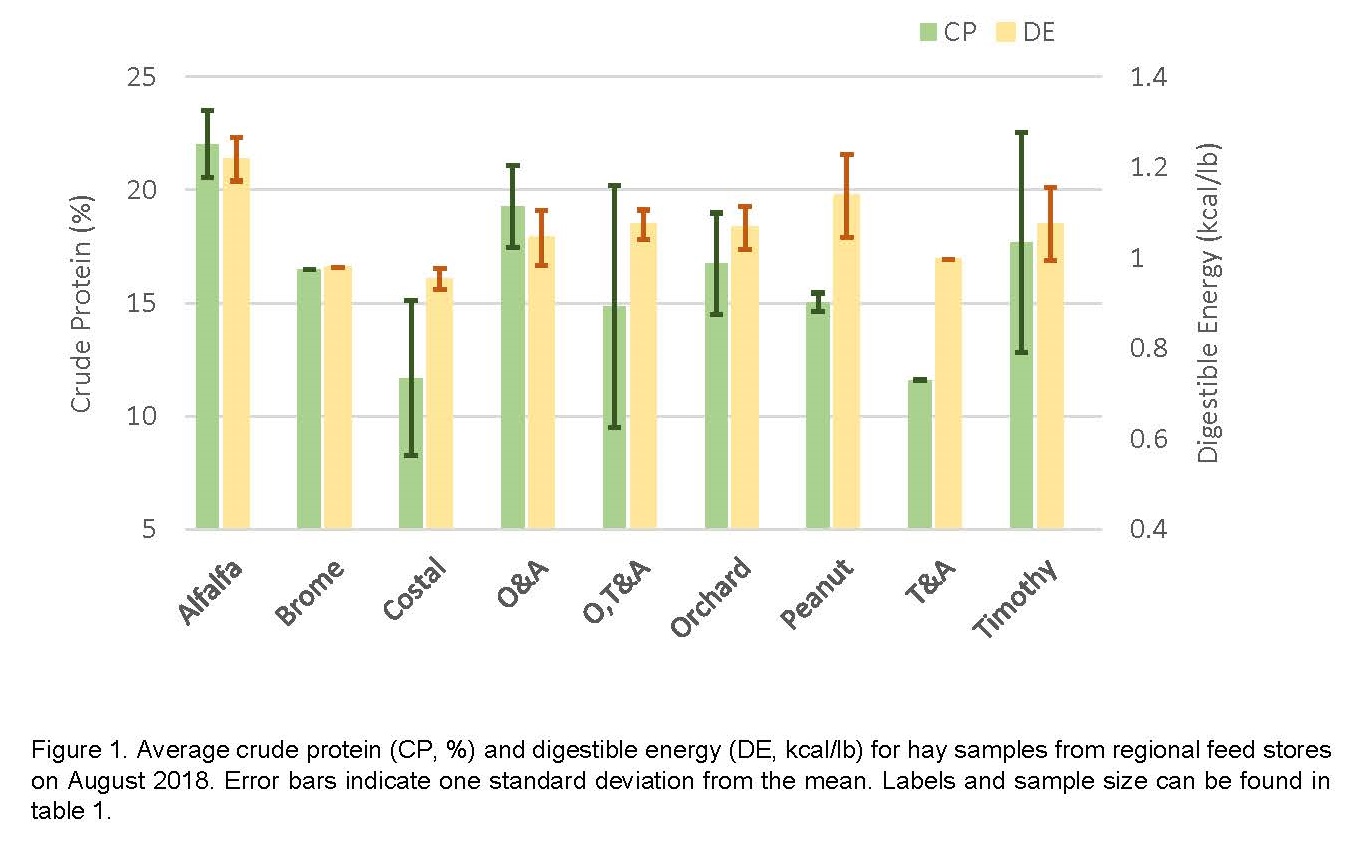

To further explore this concept, 32 hay samples which represented a range of hay types on the market were obtained from local feed stores, from imported legumes and grass hays to hay types produced in state. The goal was to quantify the key nutritional components provided by each hay in a comparative manner to allow horse owners to better evaluate their purchases on a nutritional requirement basis and an economic basis.

0

0