Spring is officially here, so it is time to start thinking about beef herd management over the next few months. If you have not yet developed a ranch calendar for 2022, you may want to look through the 2022 Panhandle Ag Team Cattle & Forage Management Calendar that was developed based on the annual management calendar for the UF/IFAS NFREC Beef Research Herd. This calendar gives general guidance on timing of different management practices, but ranch management practices vary depending on the breeding season utilized and the labor and resources available on each operation. The main purpose of this document is to serve as a guide for developing your own plan.

One of the essential areas of beef cattle herd management is ensuring herd health through vaccination, and internal & external parasite control. Depending on your calving season, cattle have either recently been or soon will be “worked.” Typically cattle are worked at least twice per year in spring and fall when the weather is decent. Like so many things we order these days, it is wise to secure the animal health products you will need well in advance. This article will provide some general recommendations, but your veterinarian can help you design the best program customized for your specific management.

–

When to Work the Herd?

Spring is the normal time for vaccinating calves, but it really varies from operation to operation. Even the names people use for this can be confusing, some call it “Spring Roundup,” others “Marking and Branding” (historic term for when calves were brought in for identification with ranch brands and ear marks), still others “Spring Cattle Working.” Use whichever phrase you like, but the main point is to prepare for the time to provide vaccinations and parasite control. Since cattle are generally worked only two to three times per year, this is also an opportunity to take care of any necessary management, such as replacing missing ear tags, and address individual animal health issues.

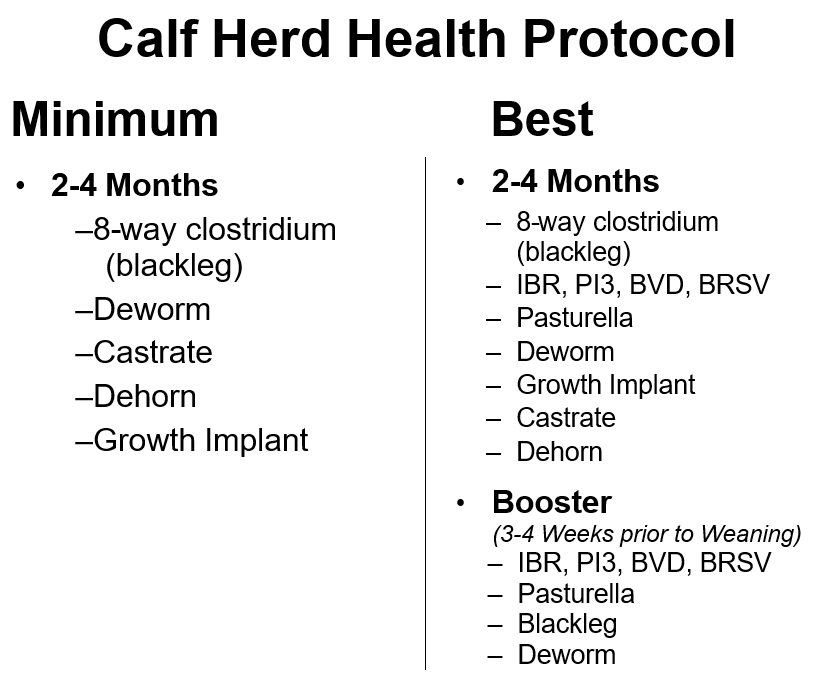

The key question though is when should this take place? It really depends on when calves are born and how the calves will be managed after weaning, but ideally calves should be vaccinated at 2-4 months of age with a booster shot prior to weaning. Most vaccines require a booster to provide full immunity, but even a single dose sets the calves up for a greater immune response when they are vaccinated after weaning. Just understand that for most vaccines one dose does not provide disease immunity. One of the real values of a defined breeding season is that you can select a good time to vaccinate for the majority of the herd. If you have a year round breeding season, then you are going to have to vaccinate at different times of the year to target the right age range. Calves that average three months old are also at a prime age to dehorn, castrate, and for growth implant insertion.

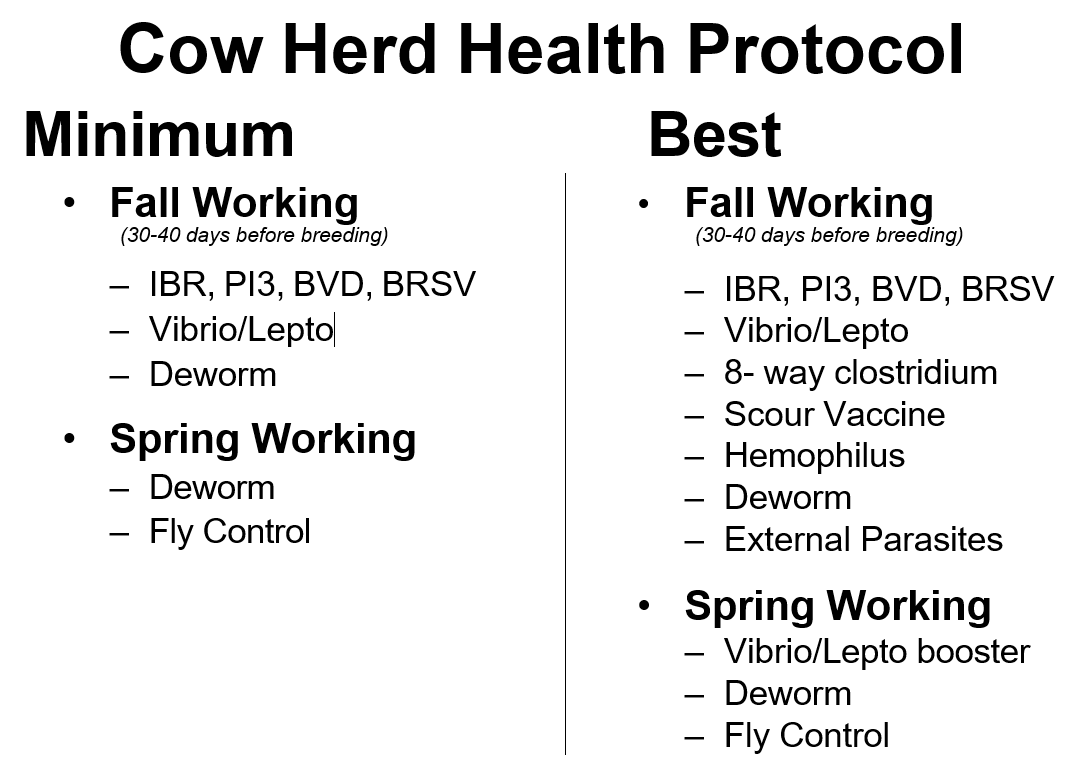

Cows need vaccination for reproductive and respiratory diseases, with a primary focus 30-45 days prior to the breeding season. For some operations, this is not a possibility, so the main idea is to at least get cows vaccinated 60 days before calving, so they pass along immunity in the colostrum (first milk). If you start calving in October, then this will not truly be in the fall, but a late summer practice. The NFREC Beef Herd calves in the winter months, so they work cows in fall to prepare for calving and breeding seasons. However, if you are bringing cows to the pens to work their calves in the spring this provide a great opportunity for parasite control.

Internal parasites are an issue in Florida pretty much year round, but are more serious when the grass is short and cattle are thinner, which translates to Spring and Fall. As cattle graze short grass they will likely consume more parasite eggs, and this is also a time when nutrition from forages is lowest. Depending on your herd health protocol, cows may not have to be vaccinated in the spring. Timing of herd health practices varies greatly from operation to operation, so the main idea is to make the most of the 2-4 times the cows are in the pens each year.

–

What shots and treatments should be provided?

When and what brand and type of health products to use is sort of like asking people what type of pickup or tractor they like best. You get a lot of different answers depending on who you ask. This is somewhat frustrating, especially if you are looking for a basic recipe. The following are some general guidelines for calf health treatments, but it really depends on how cattle are marketed as to what is best. For instance, cattle that are weaned and sold at seven months or younger at the market would be managed differently than calves than are weaned and preconditioned on the ranch 60 days before sale. This is why working with your veterinarian to develop your specific herd protocol is important. The following are examples of what might be developed with the help of your veterinarian:

–

The same holds true with when and how you work your cows. Most ranchers try to minimize the number of times cows must be penned and run through the chute, so the following are examples for a herd that was only worked twice per year.

Product Options for Health Protocols

–

Vaccines

There are a wide range of animal health products available to help maintain a healthy cattle herd. Each major animal health company has their own product lines. The main thing you want are vaccines that provide protection from reproductive and respiratory forms of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) virus, bovine viral diarrhea (BVD), as well as respiratory disease caused by parainfluenza (PI3) virus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV). You should also protect cattle against clostridial bacterial diseases, such as blackleg. More details can be found in the Alabama Extension Publication: Vaccinations for the Beef Cattle Herd.

One important thing to note is that vaccines contain either modified live (MLV), killed (KV), or chemically altered (CAV) organisms. They work by creating an immune response to a specific disease in an animal. Most require a booster shot to gain full immunity to a specific disease. Each product label provides specific instructions about the timing for a booster shot.

Modified live vaccines (MLV) contain a small amount of the actual disease resulting in a controlled infection. In general, MLVs provide the greatest immune response and the best protection against disease. They do have to be mixed on site and must be used right away, so you only want to mix what up is needed that day and dispose of any remaining contents. Some MLV vaccines can cause abortions or infertility, if they are administered incorrectly. It is very important to read the product label before use. The best approach is to vaccinate replacement heifers with MLVs after weaning, when there is no issue with infertility or abortion, to prepare the animal for future injections in their lifetime.

Killed vaccines (KV) are the safest to use in most all situations, but require two doses to build immunity. The immunity of KVs is shorter lived, and these shots can cause allergic reactions and knots on the animal because they have to cause irritation to create an immune response. These products also have a longer shelf life, so as long as they are kept cool, partial bottles can be stored for short periods for later use if need be.

Chemically altered vaccines (CAV) contain modified live organisms that have been grown in chemicals that cause mutations that make them safer than MLVs. Sort of the best of both worlds, but the immune response is not as strong as with MLVs, but is generally better than KV products. A booster will also be needed with CAV vaccines.

Whichever vaccine type you purchase, make sure you not only read the instruction for administering the drug, but also read the storage requirements. Most vaccines need to be refrigerated, but not frozen, and should not be left on the dash or bed of the truck for hours in the Florida heat. It is also a good idea to purchase a refrigerator thermometer too, if you use an older refrigerator in the barn or garage for drug storage. It is also advisable to have a small cooler with cold packs to keep vaccines cool in the cowpens, so they don’t get hot before use. You don’t want to invest the money and then have worthless vaccines because they were not stored properly from purchase to injection.

–

Internal Parasite Control

Internal parasites negatively affect the performance and overall health of cattle. They have the greatest affect on cattle with highest nutritional requirements, such as young calves, yearling stockers and replacement heifers, lactating cows, 1st-calf heifers, and older cows over nine years of age. No matter what stage of production however, feed and forge is too expensive to waste to feed parasites.

As with vaccines, there are a wide range of dewormer products that control internal parasites. There are “Pour-on” products that can be applied to the backs of cattle and absorbed through the skin. There are “Oral Drenches” that are squirted in the mouth of cattle that are restrained with an applicator. There are “Injectable” products that are given as a shot. There are even dewormer products that can be fed without the need for gathering the herd at all. Just as with vaccinations, any form of dewormer is better than none at all, but there are key times when the investment pays the greatest returns. Most product labels provide dosage recommendations based on the weight of the animal. Certainly injections are the most precise form of delivery, followed by oral drenches. Oral drenches require the greatest level of restraint. Pour-on products offer the convenience of treating animals quickly in narrow alleys with minimal constraint, but will have more variability with less accurate placement or unexpected heavy rainfall. Dewormers in feed products such as lick blocks offer the greatest convenience, but also lack dosage control. The boss cow may get more than the old thin cow that needs it most. If you already have cattle in the squeeze chute, use the most precise delivery methods.

There are a wide range of brand named products, but a limited number of active ingredients. Don’t use the same active ingredient every time. Iowa State has a nice publication that shows different types of products and the specific active ingredients: Internal Parasites of Grazing Ruminants. The main idea is to rotate active ingredients to prevent resistant parasite populations. For example, if you use an ivermectin pour-on on the cows in the spring and an ivermectin injectible when the cows are in the chute in late summer or fall, you are still using the same active ingredient. Work with your veterinarian to develop a good active ingredient rotation.

–

External Parasites

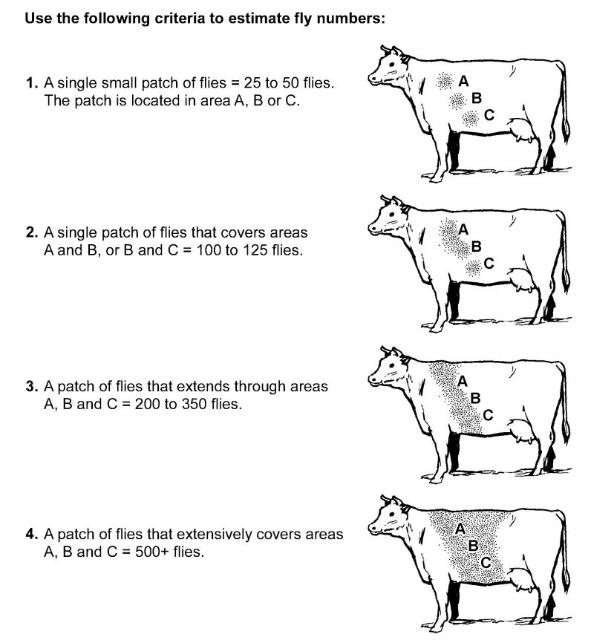

There are also a wide range of external parasites that affect the performance and overall health of cattle, especially when populations spike. Blood sucking flies, lice, grubs, ticks, and mosquitoes can all affect the health and well being of cattle, both from the bites and also as a disease vector. The difference with external parasites is that we can see the extent of the damage. Because of this, we can utilize more of an Integrated Pest Management plan for treatment. Horn flies are one of the most serious pests of cattle in Florida. You can utilize an as needed approach to fly control, and treat when there are an average of 100 or more flies on the side of cattle. Cows can be sprayed in small pens with insecticides only when they are needed to reduce the population. The other approach is to utilize products with short-duration control when the pests are most active. One example commonly used is to apply fly tags or a pour-on product at the spring working, and again at weaning.

There also a wide range of product options for external parasite control. There are topical liquid treatments such as pour-ons or concentrate liquids mixed with water and sprayed on the side and back. There are also a few injectible and pour-on products that control both internal and external parasites. Fly tags are another option for fly control, you just have to rotate active ingredients to prevent resistant populations. The tags also have to be removed after their effective life, or they can contribute to resistance development. Back-rubbers are another tool that can be used to deliver oil-based insecticides on a regular basis. The trick with them is setting them up in a place cattle pass through regularly. There are even insect growth regulators (IGRs) that can be added to minerals or other feeds that interrupt the life cycle of flies as long as cattle eat the correct amount on a regular basis. They main idea here as with the other topics, it is better to provide some form of relief than none at all. The wide range of products can be customized to fit your annual herd health protocol.

–

Heard Health Record Keeping

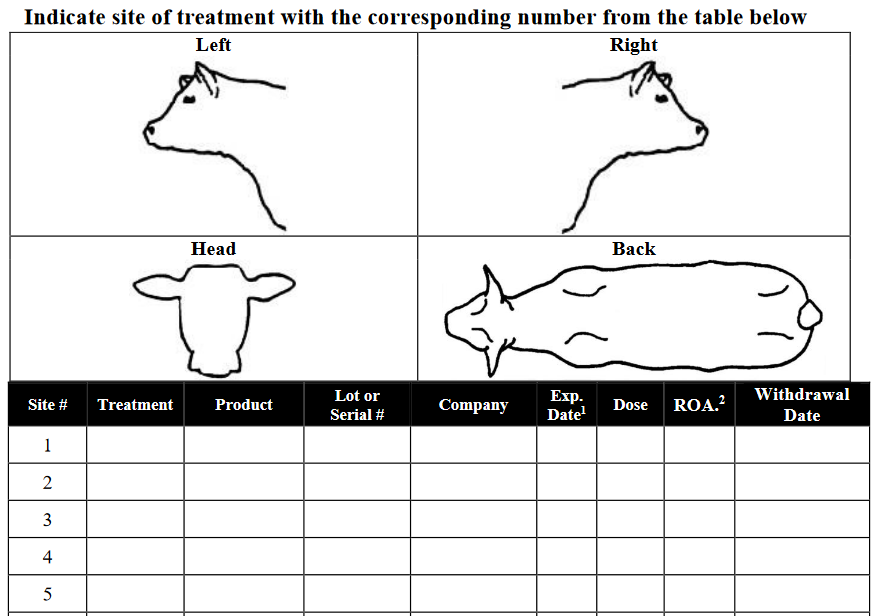

One other area that is also helpful is to keep records of the health products you purchased, and when and how the shots and treatments were administered. This is particularly important if you market cattle as a group, or by the truckload. Your records can serve of proof that the cattle have been managed well. This is also important information in case there are issues that arise with negative reactions or suspected product failure. The following are two examples of the type of heath records that should be kept on file as animal health products are purchased, and after they are administered.

One other area that is also helpful is to keep records of the health products you purchased, and when and how the shots and treatments were administered. This is particularly important if you market cattle as a group, or by the truckload. Your records can serve of proof that the cattle have been managed well. This is also important information in case there are issues that arise with negative reactions or suspected product failure. The following are two examples of the type of heath records that should be kept on file as animal health products are purchased, and after they are administered.

–

Health Product Inventory Record

–

Group Health Record

–

In Summary

I have covered a wide range of topics in this article and have not given many specific instructions. The reason is that there are so many options for developing a health protocol for your herd. Make an appointment with your local expert, a large animal veterinarian, and develop a protocol that will work best for your operation. When and how often are you willing to work your cattle? If labor is short and twice a year is your answer, they can help you set up a system for that. But, if you are bringing cattle into the pens for pregnancy tests, to wean calves, sort into groups, artificial insemination, or other management scenarios, there are more options. You really need to established a client relationship with a veterinarian for antibiotics and other medication prescriptions (not vaccines and dewormers). Build that relationship developing a health protocol, so they will already know you when you need to treat sick cattle or for assistance at calving time. Even if you can’t vaccinate and provide parasite control at the ideal time, setting aside a specific time to work cattle at least twice per year is much better than just not doing it. Preventing sickness and death with vaccines, and managing parasite populations is essential ranch management. If you need help with contact information for local large animal veterinarians, have general questions about cattle heard health, or about specific commercial product labels, contact your local county extension agent.

–

More information on this topic is available by using the following publication links:

Vaccinations for the Beef Cattle Herd (Auburn)

–

Cow Herd Vaccination Guidelines (New Mexico State)

–

Calf Vaccination Guidelines (New Mexico State)

–

Internal Parasites in Grazing Ruminants (Iowa State)

–

External Parasites on Beef Cattle (UF/IFAS)

1

1