NOTE: The Family Dairy Day at the UF/IFAS Dairy Research Unit in Hague for October 25 has been CANCELLED.

When the Florida Agricultural Extension Service started in 1915, many agricultural commodities already had a long history in the state, such as beef cattle, cotton and citrus. But in the case of dairy farming, it was virtually nonexistent when Extension arrived on the scene. In a way, you could say that Florida’s extension service and dairy industry grew up together.

Building a Dairy Industry

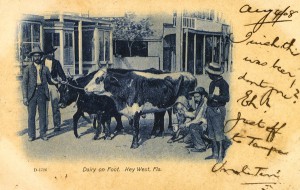

At the turn of the century, Florida had no dairy industry to speak of. The few commercial dairies in the state were small operations. Farmers only owned as many cows as they could milk by hand, and the milk was collected into steel cans and hauled by horse-drawn wagons directly from the farm to customers, or to milk distribution depots. In some areas, the “dairyman” was just a man who would lead his cow into town and milk it directly into a pail for customers.

But as Florida’s population continued to grow, the demand for fresh milk, cream and butter increased, particularly in urban centers and tourist resort areas. Small local dairies were helpless to keep up with demand. The problem was that native dairy cows, feeding on wiregrass and carpetgrass, only produced about a gallon of milk per day; in order to produce more milk, farmers had to feed their cows concentrated protein feeds such as wheat bran or cottonseed meal, which had to be bought on the market. As a result, more than half of the possible profit from producing milk went to feeding the cows. Meanwhile, cities and resorts were importing their dairy from out of state, sometimes from as far away as New York. If Florida’s dairy farmers were going to compete, they needed improved breeds of milk- producing cows and cheaper ways to feed them.

The Florida Agricultural Experiment Station began examining this problem in 1907, soon after it set up its new headquarters in Gainesville. By feeding the station’s herd of twelve Jersey and native cows various feeds, animal industrialist John M. Scott determined that milk could be produced much cheaper by feeding cows locally grown forage such as velvet beans, a legume that grew easily in Florida. Nutrient rich pasture grass could also be improved by being fermented in silos, a practice that had been used for many years in northern states. Scott also conducted breeding experiments, introducing pure-bred Shorthorn and Hereford bulls to sire more productive milk cows.

Scott took these results to Farmers Institutes and short courses around the state, and very soon an interest in dairying began to develop. When the Florida Agricultural Extension Service was established in 1915, agents were besieged by questions about how to start up dairy farms. Extension responded by pouring much of its early efforts into developing lectures and demonstrations to spread the word about alternative forages, silage and improved livestock.

Unfortunately, at that time there was a certain fly in the ointment that was preventing Florida’s dairy industry from taking off. Texas tick fever had first been diagnosed in Florida’s cattle herds in 1902, and by 1915 it was decimating livestock herds throughout the state. The USDA had developed a means to control the spread of the fever-causing ticks by dipping cows in vats of arsenic, and Extension assisted by constructing dipping vats and helping dairymen and ranchers to disinfect their herds. In some areas, the fever tick was not eradicated until the late 1920s, but in areas declared tick-free, Extension agents helped farmers form cooperatives and convinced bankers to loan the capital to buy carloads of purebred bulls and Jersey and Guernsey milk cows. Agents also helped farmers construct wood and concrete silos and silage pits around the state.

‘A Cow in Every Home’

While Extension’s field agents were busy helping commercial dairies get started, its home demonstration agents were pursuing an even more ambitious agenda by creating an expanded market for dairy and spreading the word of milk’s health benefits to Florida’s native population. Until the 1920s, the demand for milk came mainly from tourists from the north and Midwest visiting Florida over the summer months; few native Floridians had any dairy in their diet. The disparity in milk consumption was so great that when ‘tourist season’ ended each April, the bottom would drop out of the state’s dairy market, leaving farmers with surpluses and plunging prices. At the same time, health officials and Extension home demonstration agents were painfully aware of the poor nutrition they saw, particularly among children in the state’s rural population. The nutritional benefits of milk and milk products had been well established and publicized elsewhere in the country. Therefore, Extensions’ home demonstration team saw an excellent opportunity to help the fledgling dairy industry while improving the health of Floridians.

To head up Extension’s home dairy program, May Morse was appointed assistant state agent in 1917. After visiting households, fairs, and short courses around the state, she concluded that there was a “crying need” for more milk in the state, and immediately began a campaign to “put a cow in every home.”

Many extension agents quickly learned that the best way to influence adults was to reach their children first. Through canning and nutrition clubs already set up in many public schools, home demonstration agents stressed the importance of adding milk to the diet. One agent in Manatee County began a program of weighing and measuring children; those who were underweight were given a card that read, “I should weigh _____lbs.” They were encouraged to drink milk every day at lunch, and classrooms were given scales and wall charts to keep track of students’ progress.

And then there were the three white rats: Morse had designed a demonstration taking three white laboratory rats, feeding one a diet with the equivalent of a daily glass of milk, another with the equivalent of a daily quart of milk, and a third that received no milk at all. Cages with the three rats were taken around to schoolrooms and fair exhibits around the state. Morse reported that a girl from Manatee County told her that she began drinking milk after seeing the exhibit at a fair. “I did not like it at first,” she said, “but I didn’t want to look like the ‘little’ rat.” Morse added that the girl had gained three pounds within a few weeks of drinking milk.

While some of these techniques may seem somewhat heavy-handed today, they were effective at getting Florida schoolchildren to drink milk. Morse reported that after a 1921 “Milk Week” campaign in Plant City, which featured window displays, movies, booklets, posters, talks—and the three white rats—demand for milk in school lunches increased from 3 to 113 gallons daily. Extension agents collaborated with health departments and women’s clubs to bring milk campaigns to Miami, Tampa, Jacksonville and many Florida counties; local dairies reported that their sales increased 10-35 percent as a result of the campaigns.

Morse was also instrumental in organizing youth dairy clubs around the state. Like Extension’s other commodity clubs–tomato clubs, corn clubs, pig clubs, poultry clubs, among others—these precursors of 4-H used self-guided projects, contests and events to teach youth progressive agriculture techniques. In dairy clubs, members would raise their own calves, keep records of their feeding and milk production, and sell milk, butter and other dairy products. Each year, the dairy clubs would meet at the state fair to hold contests for highest milk yield, lowest cost of production, increase in dairy stock and stock improvement. The clubs also designed exhibits to promote the value of pure bred dairy stock, home grown feeds, better business methods for dairy work, and the nutritional benefits of milk.

Morse worked at building the Extension home dairy program until 1923.

Hamlin Brown

In 1921, Extension appointed its first commercial dairy specialist, Hamlin Brown, who carried on the work that John Scott of the Agricultural Experiment Station had been doing. Under his leadership, Extension advised dairymen about the best feeds for milk production, constructed silos, produced pamphlets about home dairy farming, organized 4-H club work and promoted dairy as a major part of Florida’s agriculture.

In the mid-1920s, the real estate boom hit south Florida and many dairy farmers began selling their properties to make room for new development. As a result, the number of dairy herds dwindled while the demand for milk increased, causing milk prices to soar. Again imports threatened to flood the market and undo Florida’s homegrown dairy industry. Extension responded by stepping up programs to promote more productive dairy farming. To field days and short courses, Hamlin added motor tours of local dairies so that dairymen could compare their operations and learn from each other. “Some may think the man past 30 years of age will not take on new ideas,” Hamlin noted, “but all that is needed to disprove such statements is to take a bunch of farmers and dairymen on a tour and watch them copy new ideas when they get back home.” Many farmers also began forming dairy associations, which helped develop grading systems for milk and stabilized the market for dairy products. By 1928, there were dairy organizations in 13 Florida counties. They were able to influence the Florida legislature to pass the Florida Milk Law in 1929, which established a milk grading system and protected commercial dairies against unfair competition from off-grade milk being imported into the state.

Brown worked as the Extension dairy specialist until 1947, during which time he oversaw the growth of Florida’s dairies from a few small farms to major part of the state’s economy. The 1919 US Census recorded 71,651 cows in Florida with an annual production of 1,307 pounds of milk per cow. By the 1928 census, Florida had 62,940 cows, with an annual production of 2,614 pounds of milk per cow. So while Florida had some 9,000 fewer cows, thanks to help from the Agricultural Extension Service, milk production from each cow had increased by 100 percent.

Florida Dairy Today

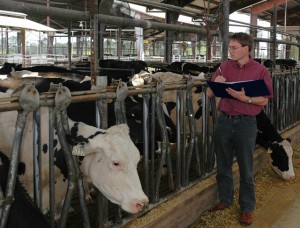

Today, Florida has 119,000 dairy cows, each producing around 19,000 pounds of milk annually, or about six to eight gallons per day. There are 138 dairy farms in the state, most with herds of about 800 cows, and most are family-owned businesses, with some families going back two or three generations in dairying. UF/IFAS Extension continues to work with Florida’s dairy farmers through the UF’s departments of animal sciences and veterinary medicine. Through newsletters, consultations, conferences and field days, Florida Dairy Extension offers research-based information that helps dairy farmers increase their milk production, keep their cows healthy and manage their operations in ways that are good for business and safer for the environment.

You can learn more about Extension and Florida’s dairy industry at these sites:

Florida Extension Dairy

http://dairy.ifas.ufl.edu/index.shtml

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services–Dairy Industry

http://www.freshfromflorida.com/Agriculture-Industry/Search-by-Industry/Dairy-Industry

Florida Dairy Farmers

Sources:

Arriola, K.G., and A. De Vries. 2013. Florida Dairy Industry Statistics: Economic Measures. UF/IFAS Publication AN 287. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/an287

Florida Cooperative Extension. 1918 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/flag/results/brief/?t=extension+annual+report&o=10

Florida Cooperative Extension. 1920 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

Harris, W. 2002. Florida’s Agricultural Heritage. Orlando, FL: Florida Agricultural Hall of Fame.

Scott, J.M. 1909. Milk Production. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 99. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

Scott, J. M. 1913. Milk Production II. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 114. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

0

0