Summer’s here, school’s out, and if you’re one of more than 230,000 4-H’ers in Florida, that means four magic words: Cloverleaf, Ocala, Cherry Lake, and Timpoochee. For the uninitiated, those are the names of Florida’s residential 4-H camps. They’re strung across the state like charms on a bracelet, each situated near a lake or by the sea, each promising a week or more of fun in the sun, on the water, or around the campfire. 4-H camps have been a magnet for youth since the early years of the last century, and they have a storied past, one which winds though forgotten chapters of Florida history like a lazy river meandering through a dense forest.

The First 4-H Club Camps

4-H has its origins in agricultural youth clubs that began organizing in Florida around 1909. The so-called “corn” clubs for boys and “tomato” clubs for girls led to “pig” clubs, “poultry” clubs and the like until they were consolidated into overall youth clubs by Cooperative Extension service beginning in 1914. The idea of holding summer learning and recreation retreats began soon after as a method for training leadership and rewarding outstanding club members. The first “Club Camps” for boys and girls in Florida were established in Hillsborough, Santa Rosa County and Brevard counties in 1919.

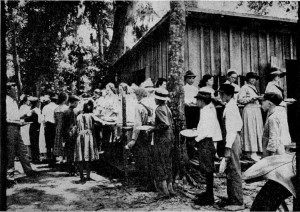

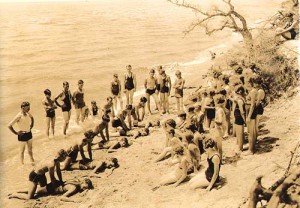

In Santa Rosa County, camp began in early June on Floridatown land bordering Escambia Bay. Girls stayed in a three-room cottage, while the boys pitched tents about a quarter-mile away. The camps were supervised by county and home demonstration agents and state workers. This schedule from 1919 offers a glimpse of what a typical day at camp was like:

- 6:30 A.M. Bugle Call

- 6:35 Setting up exercises

- 6:45 Morning dip for boys; Girls dress and clean house

- 7:30 Breakfast

- 8:15 Boys clean house; special talk to girls

- 8:30 Forenoon classes–boys and girls separate–in four sections

- Girls:

- Sewing: darning; buttonholes; talk on dress

- First aid to injured

- Fancy pack: labeling; fair exhibit; steam pressure

- Basketry: Wire grass or pine needles; needles, raffia

- 11:30 General Assembly (chapel)

- 12:30 P.M. Dinner

- 12:45 t0 2:00 Rest

- 2:00 Quiet or sitting games

- 4:30 Military Drill

- 5:00 Athletic tests and active games

- 6:00 Girls’ swim; special talk to boys

- 7:00 Supper

- 8:00 Camp fire

- 9:30 Taps

Camp Timpoochee

The chance to sleep away from home, swim and play in a co-ed environment made the club camps extremely popular. Each following year, more camps opened across the state with greater attendance, until the only feasible solution was to establish permanent, regional camps with full staff and facilities. In 1926, the Extension service leased fourteen acres of land from the U.S. Forestry Service to establish a camp on Choctawatchee Bay in Okaloosa County. Citizens and business people in northwest Florida donated $1,000 in lumber, roofing and nails to build the camp; the rest came from 4-H’ers themselves: club members in 10 counties west of the Apalachicola River each donated one fat hen raised in their poultry clubs. The hens were gathered at county seats, loaded on railroad cars and sold in Marianna, with proceeds going to the camp. As one district agent pointed out, “’A car of fat hens’ for a 4-H project is surely an object lesson in worthwhile cooperation.”

While the camp was a huge success, growing from accomodations for 60 in 1928 to more than 250 in 1934, for its first ten years it was known only as “the West Florida camp on Choctawatchee Bay.” In 1936, Rusty Grundin, a 4-H’er from Santa Rosa County, proposed a slightly catchier name: Camp Timpoochee.

The camp was named after a local Euchee Indian chief named Timpoochee Kinnard. Also known as Sam Story, Chief Timpoochee was the son of a Euchee woman and a white man of Scottish descent. In 1820, when white settlers from North Carolina first came to Walton County, Timpoochee invited them to live on his land. However, by 1832, waves of white settlers in northwest Florida were destroying the land, chasing off wildlife and causing forest fires. The Euchee were forced out of Walton County, but before the tribe began their move, Timpoochee died. After three weeks of mourning, about 500 Euchee gathered at an area known as Story’s Landing, embarked on their canoes across the Gulf of Mexico, and vanished from the pages of history.

The “New Deal” Camps: McQuarrie & Cherry Lake

4-H’s second camp, Camp McQuarrie, was established in the 1930s, a time when Florida’s youth needed respite from the harsh realities of the Great Depression. Because money was scarce, it would take more than selling hens to pay for construction. The camp was built in the Ocala National Forest by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a New Deal relief program that promoted environmental conservation while it put thousands of unemployed men to work in the nation’s forests and parklands. With only a $500 Extension budget to work with, Marion County agent Clyde Norton was able to secure funds from another New Deal program, the Federal Emergency Relief Agency, to pay for $800 worth of additional labor and materials. The University of Florida and the Florida State College for Women (later FSU) donated kitchen equipment from their dining halls. The camp, located by a lake and with room for 100 campers, opened in 1934; it was named Camp McQuarrie after C.K. McQuarrie, Florida Extension’s first statewide demonstration agent.

By the late 1930s, conditions at Florida’s two camps became so crowded that 4-H undertook a third camp on the shores of Cherry Lake in Madison County. The land for Camp Cherry Lake was acquired from the Florida Rural Rehabilitation Corporation (FRRC). A joint federal-state relief effort, the FRRC bought land, divided it into forty- to sixty-acre plots of farmland, and mortgaged it at low rates to farmers and indigent families ruined by the depression. Much like the rural relief camps made famous by John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath, in the 1930s Cherry Lake Farms was a thriving colony, with a canning plant, 2,640 acres of community-owned farmland, and hundreds of two-bedroom, one-bath houses where families from across the country came to start a new life. The Cherry Lake Corporation donated 12 acres of land on the west side of the lake, high-school and college-aged men and women from the National Youth Administration (yet another New Deal agency) began construction with lumber salvaged from an abandoned labor camp, and several counties donated cash for materials and equipment. Thanks to hard work, community spirit and generosity, Camp Cherry Lake opened to its first 100 4-H campers in 1937.

Camp Doe Lake

4-H’s next camp, at Doe Lake in the Ocala National Forest, was a product of the era of racial segregation in Florida. From the period following the Civil War up until the mid-1960s, many institutions in the South maintained separate facilities for blacks and whites. Segregation even applied to bodies of water: In 1939, when African-Americans visiting from the North were found swimming in Juniper Springs, it prompted so many complaints from white bathers that the Forest Service and the CCC worked to establish a separate recreation area for blacks. The area around Doe Lake in Madison County was chosen because in addition to its clear waters and good fishing, it was isolated enough to reduce friction from the white community. Nevertheless, when the camp opened in 1940, many local whites were outraged that their prized fishing spot had been taken away from them. Hostilities may have prevented many black campers from using the site. “The black experience at Doe Lake was interrupted during the 1940s,” concludes a 1989 Forest Service study, “victim either to pressure from local residents or disinterest and neglect by the black community.” Local Boy Scout troops used Camp Doe Lake until the late 1940s, when it was acquired as a 4-H camp.

At that time, 4-H was also segregated; facilities at camps Timpoochee, McQuarrie and Cherry Lake were meant only for white campers. Black 4-H clubs had to use temporary camps on the grounds of black colleges or areas sponsored by private citizens and businesses. In Leon County, for example, 4-H’ers held camps at Lake Hall on property loaned by Charles Paynes, a black farmer. It took persistent lobbying from black farm and home demonstration agents to secure a permanent 4-H camp of their own.

Camp Doe Lake was opened as a 4-H camp for African-American campers in 1949. That summer, it welcomed 263 girls and 175 boys, who came from every part of the state to enjoy swimming, canoeing and fishing and attended demonstrations on first aid, hygiene, water safety and citizenship. The camp hosted many programs and special guest speakers over the years, and it was the main statewide meeting place for African-American clubs until 4-H was desegregated in 1964. After that, Doe Lake was open to 4-H campers of all races until it was closed in 1972.

Camp Cloverleaf & Camp Ocala

Extension leaders had long recognized the need for a permanent camp to serve south Florida, so in 1948 when thirty acres of land in Highlands County was donated to the state, district agents worked hard to procure it for 4-H. Construction on the new camp near Lake Placid was begun in 1950. It opened for camping the next year, but unlike other 4-H camps, it was built up slowly over time, operating with limited facilities, and wasn’t officially dedicated as 4-H Camp Cloverleaf until 1958. In 1956, Cloverleaf hosted the first summer camp for 4-H clubs from Florida’s Seminole Indian tribe. Extension work had just gotten under way with the Seminoles, and the camp was an opportunity for campers and counselors to learn about each other’s culture. One afternoon during that first camp, all the boys in the group turned up missing. A search of the cabins, camp grounds and surrounding area turned up empty. Finally, someone found the boys swimming almost half a mile off shore of Lake Francis. A rowboat was sent out to rescue them, but the boys, having grown up in the swamps and canals of the Everglades, were excellent swimmers and easily paddled back to camp.

The closing of Camp McQuarrie in 1966 and Camp Doe Lake in 1972 left 4-H without a permanent site in central Florida for more than a decade. Finally, in 1983, the University of Florida signed a lease with the Forest Service, and Camp Ocala became the latest and largest of the 4-H residential camps. Located on the shores of Sellers Lake, Camp Ocala has cabins to sleep 220, a dining hall seating 180, conference rooms, pavilions, an interactive nature center complete with a library, museum and classroom, and a large fire circle for evening ceremonies.

In 2008 Camp Ocala hosted Florida 4-H’s first specialty camp for youth in military families. Operation: Military Kids (OMK) is a partnership between 4-H and the U.S. armed forces to provide support for families that find themselves “suddenly military” when parents are deployed for duty. In its first year, Camp Ocala hosted 83 youth from 27 Florida counties–it was so successful that all 4-H camps developed OMK programs, and a second program for military families, Camp Corral, was added in 2012.

4-H Camps Today

For more than 80 years, 4-H residential camps have been one of the most important and effective ways of reaching Florida’s youth through outdoor activities and hands-on, learn-by-doing education. 4-H camps are staffed by more than 250 youth counselors, Extension agents and caring adult volunteers. Each year, between 3,000 and 4,000 boys and girls spend a week or more at camp, learning new skills, developing self-confidence and compassion, making lifelong friends and having lots of fun. Florida and 4-H have come a long way over the past 80 years, but one thing has remained constant: as long as there are summers, 4-H’ers will be gathering around the campfire.

You can learn more about Florida’s 4-H Camps at:

…And follow the fun on these social media sites:

Sources:

Beatty, L. 2006. A Brief History of America’s Rural Rehabilitation Corporations. NARRC. http://www.ruralrehab.org/briefhistory.html

Berry, S. 1991. “Lake’s quiet was ruffled by changes.” Orlando Sentinel, October 20. http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1991-10-20/news/9110200091_1_lake-county-dining-hall-doe-lake

Cooper, J. F. 1976. Dimensions in History: Recounting Florida Cooperative Extension Service Progress, 1909-76. Gainesville: Alpha Delta Chapter, Epsilon Sigma Phi.

Cotton, B.R. 1982. The Lamplighters: Black Farm and Home Demonstration Agents in Florida, 1915-1965. Tallahassee, Florida A&M University.

Florida 4-H. n.d. History of Camp Timpoochee. http://florida4h.org/about/history/florida/history-of-camp-timpoochee/

Florida Cooperative Extension. 1919 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/flag/results/brief/?t=extension+annual+report&o=10

___. 1927 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

___. 1929 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

___. 1934 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

___. 1939 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

___. 1948 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

___. 1950 Annual Report. Gainesville: University of Florida.

Wikipedia contributors, “Sam Story,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sam_Story&oldid=529182408 (accessed June 12, 2014).

Wilson, J.S. and Lok, L.C. 2008. Florida 4-H: A Century of Youth Success. Virginia Beach, VA : Donning Co.

0

0