Welcome back to FSHN Research Journeys, which follows the research of graduate students in the Food Science and Human Nutrition program at The University of Florida. Today’s guest poster is Nick Wendrick, a first-year student working toward his master’s degree in food science. Working in the lab of Dr. Katherine Thompson-Witrick, Nick is studying the properties of canned muscadine wine over time to determine its potential in expanding the wine market. Read on to learn about his background in the alcoholic beverage sector, his growing interest in fermentation science, and his unique competitive sport.

Welcome back to FSHN Research Journeys, which follows the research of graduate students in the Food Science and Human Nutrition program at The University of Florida. Today’s guest poster is Nick Wendrick, a first-year student working toward his master’s degree in food science. Working in the lab of Dr. Katherine Thompson-Witrick, Nick is studying the properties of canned muscadine wine over time to determine its potential in expanding the wine market. Read on to learn about his background in the alcoholic beverage sector, his growing interest in fermentation science, and his unique competitive sport.

Nick: Imagine you’re hanging out with your friends while enjoying one of your favorite outdoor activities such as sitting poolside, soaking up the sun at the beach, or watching your favorite sports team. Reaching into the cooler, you realize there is only water and beer. You pull your hand away, saddened by the lack of wine in the cooler but aware that a glass wine bottle could become a hazard if it broke. Another friend shows up late to the party bringing a pack of canned muscadine wine. Ecstatic, you grab a can and pop the top. As you sip your wine, you mull over how cool of an idea canned wine is, as it allowed you to savor your favorite outdoor beverage.

Glass? Not All It’s Cracked Up to Be

The typical consumer is familiar with wine bottled in glass. Yet many consumers may not be aware of the advantages of aluminum cans compared with glass. Aluminum cans are a recognizable package, a superb barrier to light and oxygen, easily recyclable, lightweight, and don’t break into hazardous shards. Nearly all beaches, pools, and sporting events prohibit glass containers, making canned wine an attractive alternative.

In addition, a typical wine bottle contains 750mL of wine, which is equivalent to approximately five standard wine glasses according to the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB).1 Canned wine contains, on average, 355mL of wine in each can, which the TTB accepted in 2020 as a new container size for wine. At less than half the volume of a typical wine bottle, canned wine is a smarter option for many adults who are interested in consuming less wine. Canned wine sales have grown from two million in 2012 to 253 million as of March 2021, demonstrating an opportunity for canned wine to grow wine sales.2,3

There has been little research done on the potential influence of cans on muscadine wine over time. The interaction between muscadine wine and the can may affect how the wine changes over time, possibly enhancing or detracting from the quality. Muscadine grapes possess a potent mixture of health-benefiting phytochemicals compounds such as tannins, phenolics, stilbenes, flavonoids, and an array of anthocyanins.4,5 Understanding how these compounds change over time in cans compared to bottles will benefit both the consumer and winemaker.

Nick’s Journey to Food Science and Fermentation Science

I got my start in the alcoholic beverage sector when I interned at Bacardi working in the food product development lab as a beverage scientist intern. During my internship, I helped make many alcoholic beverages from ready-to-drink carbonated spritzers to ready-to-serve alcoholic cocktails such as zombies. Many of these beverage creations were either for shelf-test analysis, which tests to see how well a product maintains quality over time, or evaluated by a UF sensory panel.

The knowledge gained during my internship led me to accept a role as an undergraduate researcher in Dr. Andrew MacIntosh’s laboratory. In my research project, I investigated the effects of carbonation on muscadine wines from wineries around the state of Florida.

Over the course of a few months, with the help of Dr. Charles Sims, I ran six sensory panels in which I served 462 panelists and poured over 2,400 samples of wine. I found that the value-added process of carbonation led to a significant increase in likability, purchase intent, and ranking for the carbonated wine samples over the uncarbonated wine samples.6

This research on wine carbonation led to an opportunity to continue researching muscadine wine while attending graduate school. My previous and current research demonstrates my passion for food science and beverage research. I enjoy understanding the processing, chemical, and microbial aspects of different beverages, both alcoholic and nonalcoholic.

Popping the Top on Canned Wine

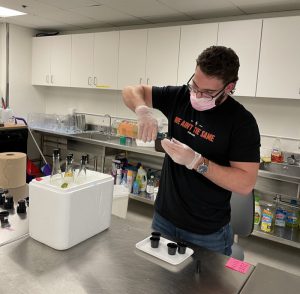

My research project contains two objectives to help the muscadine wine industry. The first objective is to compare muscadine wine packaged in glass with wine in aluminum cans. I will perform a shelf-life study, analyzing the wine’s physiochemical properties over time.

The second objective is to study how muscadine wine changes at ambient temperatures over a nine-month period. I will use analytical chemistry methods to quantify volatile and non-volatile compounds related to flavor, taste, and nutraceutical properties.4,5 By testing and measuring these essential parameters, I hope to create a complete picture of all the interactions and changes at the microscopic and chemical levels.

The results of my research will help wineries determine if canned wine is appropriate for their product portfolio. From March 2020 to March 2021, canned wine sales grew 62%, and Sans wine Co.’s owner, Jake Stover, notes, “There is so much room for growth.”3 Like my undergraduate project in wine carbonation, my graduate research project may yield another value-added process that will help increase the popularity of muscadine wine. After my research concludes, I will have a greater understanding of how muscadine wine changes in cans, allowing consumers to appreciate the same wine in a new way at every outdoor activity.

Nick Wendrick is a first-year master’s student at UF. He is using his background in fermentation to study muscadine wine packaged in cans and is a competitive axe thrower.

References

- (2021). https://www.ttb.gov/labeling-wine/wine-labeling-net-contents

- Romano, A. (2021). Is Canned Wine Growing up? Wine Spectator. https://www.winespectator.com/articles/is-canned-wine-growing-up

- Weed, A. (2020). Canned Wine Sales are Bursting at the Seams. Wine Spectator. https://www.winespectator.com/articles/canned-wine-sales-are-bursting-at-the-seams

- Li, R., Kim, M.-H., Sandhu, A. K., Gao, C., & Gu, L. (2017). Muscadine grape (vitis rotundifolia) or wine phytochemicals reduce intestinal inflammation in mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 65(4), 769–776. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03806

- Zhang, Y., Chang, S. K. C., Stringer, S. J., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Characterization of titratable acids, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activities of wines made from eight Mississippi-grown muscadine varieties during fermentation. LWT, 86, 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2017.07.038

- Wendrick, N. A., Sims, C. A., & MacIntosh, A. J. (2021). The effect of carbonation level on the acceptability and purchase intent of muscadine and Fruit Wines. Beverages, 7(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7030066

Looking for more posts exploring graduate research projects in the Food Science and Human Nutrition Department at the University of Florida?

Dive into the Research Journeys of other graduate students below.

M.S. Food Science

M.S. Nutritional Sciences

Ph.D. Food Science

Ph.D. Nutritional Sciences

2

2