By Ronit Amit, PhD, Wildlife Ecology & Conservation Department

The return of Florida panthers (Puma concolor coryi) from the border of extinction can be seen as a conservation success in terms of increasing genetic diversity and population size, but the road to a full recovery and removal from the endangered species list has not been completely paved. Previously legally hunted, the panther population was thought extinct by the 1950’s, until some 20 or 30 individuals were rediscovered roaming South Florida in 1973. Dr. Madelon van de Kerk, advised by Dr. Madan Oli at the University of Florida, Department of Wildlife Ecology & Conservation, is part of a team that has been tracking panthers since 1981 in order to study changes in the panther population.

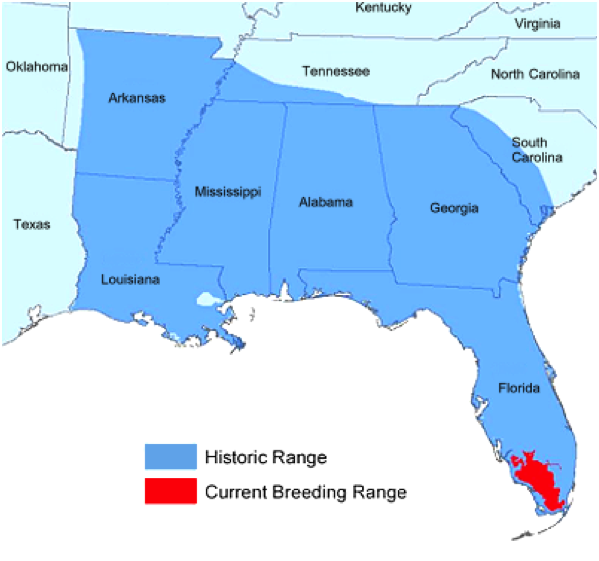

Florida panthers have a shorter coat and are smaller than other puma subspecies. However, panthers have the largest hind legs of any cat in proportion to their bodies. Some skull characteristics, such as flat, broad, arched nasal bone, also distinguish panthers from other pumas. The current breeding population of panthers resides in just 5% of its historical range and is isolated from other puma populations in the western U.S. Besides South Florida, there is no other place east of the Mississippi river that holds a breeding population of pumas. Without new individuals arriving from other populations, close relatives mate with each other, resulting in inbreeding. Inbreeding reduces the pool of alleles for the population to stay healthy and evolve with environmental changes. In the Florida panther population, biologists observed kinked tails, undescended testicles, low sperm count, heart deformities, and other genetic traits associated with inbreeding, potentially causing problems for panther survival.

Florida panthers have a shorter coat and are smaller than other puma subspecies. However, panthers have the largest hind legs of any cat in proportion to their bodies. Some skull characteristics, such as flat, broad, arched nasal bone, also distinguish panthers from other pumas. The current breeding population of panthers resides in just 5% of its historical range and is isolated from other puma populations in the western U.S. Besides South Florida, there is no other place east of the Mississippi river that holds a breeding population of pumas. Without new individuals arriving from other populations, close relatives mate with each other, resulting in inbreeding. Inbreeding reduces the pool of alleles for the population to stay healthy and evolve with environmental changes. In the Florida panther population, biologists observed kinked tails, undescended testicles, low sperm count, heart deformities, and other genetic traits associated with inbreeding, potentially causing problems for panther survival.

To save Florida panthers, wildlife agencies have protected panther habitat, managed the panther’s prey base (e.g. whitetail deer Odocoelius virginianus), built road underpasses, and performed a major intervention: releasing eight female Texas cougars (Puma concolor stanleyana) in the panthers’ breeding range from 1995-2003. This measure is referred to as genetic introgression or genetic rescue.

Madelon’s research reviews the long term persistence of the effects of this genetic introgression, and assesses future conservation planning.

In addition to routinely chasing panthers, setting radio and GPS collars, and handling adults as well as kittens, Madelon also analyzed an impressive accumulation of data. She first compared expected inbreeding traits and population demographics with an assessment done in 2007. Her findings showed that the benefits of genetic introgression seemed to persist with time, and panther numbers are now somewhat stable, reaching around 130 individuals. Researchers have tracked the new generations of panthers, and they have found that offspring of a panther father with Texas puma mother displayed reduced physical abnormalities and increased rates of survival. This finding suggests the intervention was a success for the long-term recovery of panthers.

Madelon used individual-based models to assess population dynamics in terms of heterozygosity as an indicator of genetic diversity. These models incorporate how panther individuals interact with each other and their environment while including an estimator of genetic variability and genetic stochasticity. Madelon set the current level of heterozygosity in the population in order to assess potential scenarios: what would happen to the panther population if no new individuals are introduced, or with different levels of introgression?

Her hypothesis is that increasing genetic diversity, through means of future genetic introgressions, will increase panther survival. As expected, the model shows that as more individuals are introduced, and with a higher frequency of introductions, the risk of panther extinction decreases. However, researchers must consider that there is potential for the genetic and physical traits specific to Florida panthers to be lost to the genome of the introduced panthers. To further obscure potential management scenarios, cost issues need to be accounted for as well as threats to the big cats, such as continuing habitat loss to human development and fragmentation caused by the building of new roads through panther habitat.

In conclusion, evidence suggests Florida panthers need genetic introgression for long-term survival, and the benefits of such an intervention are durable. Panthers serve as top predators in their ecosystem and are therefore considered critical to regulating biodiversity. Panthers are an umbrella species, meaning that when people protect panther habitat, many other species benefit.

These issues intrigue Madelon, and her future research may address questions pertaining to cost analysis of conservation planning.

No doubt we look forward to her future research (follow her on Research gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Madelon_Kerk).

0

0