4-H and Extension go way back. In fact, they go back to the very roots of both demonstration work and the rural youth development movement. In the early 1900s, when researchers and educators from the nation’s land-grant universities brought new agricultural techniques to rural communities, they often found adults unwilling to listen. Youth, on the other hand, were more eager to put new ideas to the test. Around the country, demonstration agents began reaching out to public schools, giving young men and women practical, hands-on learning which they hoped they would pass on to their parents. These efforts were so successful that when the Smith-Lever Act created the Cooperative Extension Service in 1914, youth development was an official part of its mission.

Corn Clubs, Tomato Clubs, Farm Makers and Home Makers

In Florida, 4-H youth development begins in 1909 with J.J. Vernon, UF’s Dean for Agriculture. Vernon organized a group of Corn Clubs for boys in Alachua, Bradford and Marion counties. Boys were given hybrid corn seed and shown how to prepare and plant their fields; cash prizes were given to the boys who produced the most corn, with special prizes for those whose crops out-produced their parents. The chance to learn by doing something on their own, as well as promise of winning a prize, made the corn clubs instantly popular. By 1914, when Florida’s Agricultural Extension Service began managing the corn clubs, there were 935 boys enrolled in clubs in 36 counties. The corn clubs soon spawned clubs for other commodities such as swine, cotton, sweet potatoes and poultry.

Source: ICS photo archives.

To match the success of the boys’ corn clubs, Tomato Clubs for girls were organized by Agnes Ellen Harris in 1912. In the tomato clubs, young women planted 1/10th of an acre with tomato seeds, which they grew, harvested and canned. By 1914, 373 girls were enrolled in tomato clubs. The canned tomatoes often brought in extra money for the household, and even enabled a few of the girls to enter college.

Source: Florida 4-H photo archives.

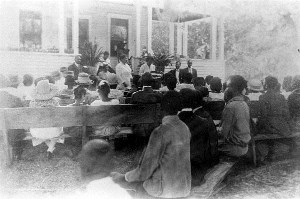

As was common in the South at the time, Extension work was racially segregated, and this extended to youth club work. In 1915, A.A. Turner organized Florida’s first youth clubs for African-Americans, with Farm Makers’ Clubs for boys and Home Makers’ Clubs for girls. Each boy in the Farm Makers’ club learned to cultivate one acre of land, planted one-half in corn, a fourth in sweet potatoes and a fourth in peanuts. In Home Makers’ clubs, girls cultivated 1/10th of an acre, planted in tomatoes, okra and beans. The purpose of these clubs, Turner noted, was to encourage a habit of reading, bring school life and home life closer together, and prepare young men and women to enter courses at Florida A & M College. By 1918 there were 2,122 youth active in clubs in 18 counties.

Source: State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/63164

An important part of these early youth clubs was the short course, a statewide conference where the members of the various county clubs met to attend lectures, learn new techniques, and form bonds. Extension agents often packed a train car or automobile with the clubs’ contest winners and navigated the state’s dirt roads to Gainesville or Tallahassee for that year’s short course.

4-H in Clover

Across the nation, youth clubs continued to grow throughout the 1910s and 20s. And as the clubs began offering more, the ‘learn by doing’ educational philosophy of the early years shifted its emphasis from raw production to one of personal development. Concepts like self-improvement and community service became as important as how many pounds or corn or canned tomatoes you produced. Moreover, as the youth clubs gained in membership and influence, it became clear that they needed a common identity.

Since 1907, a clover emblem had been circulating through various youth clubs around the country. Designed by Oscar Benson of Iowa, the clover had three leaves, representing ‘head,’ ‘heart’ and ‘hands,’ for the virtues of education, loyalty and service. In 1911, when Benson was working as a national club director, he suggested the emblem, adding a fourth leaf representing ‘hustle.’ The four-leaf clover emblem gained in popularity–though ‘hustle’ was later replaced with ‘heart’–and it soon became the symbol of the youth club movement. The “4-Hs” of club service were first mentioned in 1918, and by 1924, the various tomato, corn, farm makers’ and home makers’ clubs became officially known as 4-H Clubs.

Along with the name and the emblem, a 4-H pledge was written in 1918 by Otis Hall of Kansas:

I pledge my head to clearer thinking,

My heart to greater loyalty,

My hands to larger service,

and my health to better living,

for my club, my community, my country, and my world.

Today, many of us can still recite that pledge by heart, and as a symbol of the nation’s largest youth development organization, the 4-H clover is as recognizable as the red cross or the olympic rings.

For more information about Florida 4-H, visit http://florida4h.org/about/

Sources:

Florida 4-H History Timeline. (n.d.) Florida 4-H. Retrieved December 2013 at http://florida4h.org/news/Promotional%20Kits/files/History_Timeline.pdf

Turner, A.A. (1919) Farm and Home Makers’ Clubs. University of Florida Division of Agricultural Extension, Bulletin 19. Retrieved December 2013 from http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF90000447/00001/2x?search=demonstration+%3dwork.

4-H. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 2013 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4-H

0

0