~A look at National Estuary Programs on Florida’s Gulf Coast and 5 things we can do to protect them

If you live in Florida, chances are you have a water story. Whether it involves childhood memories of a day at the beach, water skiing on the lake, canoeing down a tea-colored river, or simply admiring a Gulf Coast sunset, you know that water is what we do here in Florida. My Florida water story most strongly centers around a Pinellas County beach on the Gulf of Mexico. When our family moved to Florida 11 years ago, we came from the Wasatch Mountain range of Provo, Utah. On that Pinellas County beach on just our second night here, our three boys splashed in bathtub-warm waves in front of a Gulf Coast sunset. From Utah to Florida, we had moved from one beautiful landscape to a very different beautiful landscape! Years later, I often sit on that same beach and gather my emotions after visiting my mother, who has Alzheimer’s Disease and lives in a nearby care center, no longer able to recognize who I am. I’m grateful for a beautiful place to reflect and remember and recharge.

I know Floridians all have their own Florida water story, and that’s part of why I love my job to help preserve and protect Florida’s water resources. Earlier I wrote about some of the Big Issues in water management for our Extension District. These included the water use caution areas and the number of impaired water bodies in our area. Today’s blog focuses on the next Big Issue: our three National Estuary Programs.

There are 28 estuaries nationwide that are designated by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as being Estuaries of National Significance, and 4 of those are in Florida, giving us more than any other state. Of those, 3 are right here in our Extension District: Tampa Bay Estuary, Sarasota Estuary, and Charlotte Harbor Estuary.

Look below at some of the remarkable services we get from these 3 remarkable places, and you’ll see why they have “national significance.”

Tampa Bay National Estuary Program

- The Tampa Bay Estuary is the largest estuarine watershed in Florida.

- Its beauty attracts more than 5 million tourists every year–who collectively spend about $3.7 billion per year in the local economy.

- Its seaports bring in $15 billion to the local economy and support 130,000 jobs.

- It provides critical habitat for over 200 species of fish, 40,000 nesting pairs of 25 species of shore birds, and one-sixth the wintering population of the Gulf Coast’s Florida manatees.

Sarasota Bay National Estuary Program

- The Sarasota Bay Estuary is habitat for over 1,400 native species of plants and animals.

- 1 in 17 jobs in the watershed are related to Sarasota Bay–this translates to $731 million in earnings and 21,000 jobs.

- Nearly 7.5 million tourists to Sarasota Bay spend a total of approximately $1.5 billion dollars per year.

- Visitors and local residents alike make over 12 million trips to Sarasota Bay every year, deriving recreational benefits from activities like fishing, snorkeling, biking, and bird watching.

Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program

-

Photo source: IFAS Communications The Charlotte Harbor National Estuary is habitat for 452 fish, 331 bird, 2,100 plant, 39 mammal, 67 reptile and 27 amphibian species. That’s a lot of diversity!

- Charlotte Harbor is highly influenced by riverine flows, from the Peace, Myakka, and Caloosahatchee Rivers. Colored dissolved organic matter from the rivers gives the Harbor a dark tea color in the summer.

- Charlotte Harbor’s beaches are internationally famous for seashelling.

- Charlotte Harbor produces about $1.8 billion in recreational benefits, 124,000 jobs, and about $3.2 billion in total income to its watershed.

So Much Success, So Much Still To Do

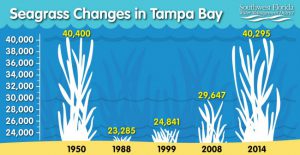

In many ways the story of our three Estuary Programs is a story of success. Long-time Gulf Coast residents know these waterbodies displayed high levels of degradation in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. One of the biggest pollutants causing that degradation was nitrogen, an essential plant nutrient but the perfect example of “too much of a good thing” when found in excess in aquatic ecosystems. Excess nitrogen in the estuary can encourage algal growth, which leads to fish kills and turbid waters. The increased turbidity blocks sunlight from reaching underwater seagrass. The seagrass is important ecologically and economically because it is teeming with life–it’s important nursery habitat for groupers, snappers, bay scallops, and shrimps. Reduced sunlight in turbid estuarine waters once caused widespread decline of these crucial seagrass beds. But as seen in the example image below for Tampa Bay, water clarity and seagrass coverage has recovered in all three Estuary Programs, thanks mostly to efforts in the 70s through 90s to reduce point source nitrogen loads to coastal waters.

Save a Lot of Money by Keeping Nitrogen out of Stormwater

Stormwater runoff from urban and residential lands is currently identified as the largest source of nitrogen in our west coast estuaries. In order to “hold the line” on seagrass recovery and potentially reduce outbreaks of harmful algal blooms we need to continue nitrogen reductions in stormwater. Florida DEP estimates that it costs $3,500 per pound to remove nitrogen from stormwater, so a clear best practice is to eliminate nitrogen loading at the source–before it enters the stormwater load. Sources of excess nitrogen include urban fertilizers, pet waste, atmospheric deposition, and organic plant detritus (grass clippings, for example) left on sidewalks and driveways.

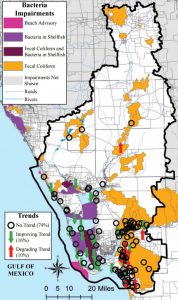

Bacterial Pollution

Nitrogen is not the only pollutant of concern in our estuaries. The image here shows areas within the Charlotte Harbor watershed where bacteria are a major concern. For example, areas in orange represent surface water bodies impaired by dangerous levels of fecal coliform. Sources of fecal bacteria include malfunctioning septic systems, leaking sanitary sewers, confined animal feedlots and untreated waste from wastewater plant overflows. Other sources such as urban pet waste and stormwater can be significant sources, especially after a heavy rainfall. For this reason, many shellfish areas are closed immediately after a large rain event.

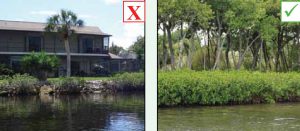

Don’t Trim the Mangroves!

Habitat loss is also a concern within our estuarine watersheds. Nearly 50% of predevelopment wetlands have been lost, and thousands of acres of our freshwater wetlands have been overtaken by the non-native melaleuca plants. In many coastal areas, native mangroves are degraded by urban residents who trim the mangroves to allow shoreline views. Mangroves thrive best when they are not trimmed–cutting them harms the estuarine shoreline and threatens the animals that depend on mangroves for feeding and breeding habitat.

Too Much, Too Little

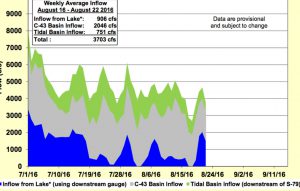

Our west coast estuaries are also heavily impacted my hydrological changes that have altered the natural flows of the rivers that feed them. This is seen in all three of our National Estuary Programs but is perhaps most prevalent in the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program because of the drastic changes made to Caloosahatchee River flows. The flow of this river is no longer controlled by nature. Dredging has straightened and deepened the river, damaged its many oxbows and connected it to Lake Okeechobee. Numerous structures allow the water flow to be controlled for water supply and boat traffic. These alterations leave the river without enough water flow in the dry season and too much water flow in the wet season. Furthermore, these changes to flow alter the natural salinity of the water in the estuary, which has significant impacts on the aquatic species that live there and depend on more natural salinity levels to thrive. Data from the SFWMD shows that:

After the locks were constructed in 1965, minimum monthly flows of 300 cubic feet per second (cfs) were reached in only four years of the last 44. More than 20% of months exceeded unhealthy average flows of 2,800 cfs.

Stewardship Gaps: 5 Things You can Do!

- Continue to grow your FFL programs. Florida Friendly Landscaping is a tremendous benefit to our estuaries. Replacing turfgrass with native plants and reducing needs for fertilizers help reduce nitrogen transport to waterbodies. Remember it costs ~$3,500 to remove nitrogen from stormwater, and your FFL programs can help residents keep nitrogen out of stormwater in the first place.

- Educate residents about septic system maintenance and boat pumpouts. Improperly sited or poorly maintained septic systems, as well as sewage waste from marinas, can be major sources of both nitrogen and bacterial contamination. Septic systems should be pumped and inspected every 3 to 5 years. EPA has a great septic system outreach toolkit that you can use to begin a program in your own area.

- Educate shoreline residents about the importance of untrimmed mangroves. You could combine this with a program about native plants and awareness of the problems associated with non-native species such as the melaleuca. (Most areas require a permit to trim mangroves–find out about laws in your local area.)

- Learn about and educate residents about programs designed to purchase lands for environmental protection. Be a voice of sound science on local land use issues, so citizens can be informed of good science when they vote on these things.

- Educate residents on the connections between soil and water quality. Help people see how they can prevent soil erosion and the transport of pollutants to water by using mulch layers and ground covers. Teach them that all the fertilizer in the world won’t make plants thrive that are planted in unsuitable soil or make bare spots in the lawn suddenly produce lush grass.

0

0